Today’s lesson will concern a very important aspect of figure drawing, that is the classic layout for the Idealistic Figure proportions.

There are many, many artists who launch into their careers, and even find some success, without properly understanding this fundamental rule. These artists (usually new youth artists) work from the principle of ‘excitement’ and (as one art instructor in my past named it) the “hot-lick” approach to drawing. This yields very stylized art with no staying power outside of nostalgia. It is a glam-based approach, and it appears very absurd when viewed outside of its own time, context, or by viewers not keyed into the paradigm the art participates in. No matter how popular it may be in its day, a few years in the future will show this type of ‘hot-lick’ art to look as absurd as a very dated hairstyle or a funny old fashion trend. It is a ‘pop’ version of drawing, and it is not advised.

The proper approach is to recognize that there are eternal proportions, established both traditionally and mathematically which imbue a subject with a virtue, a quality which subconsciously works on the viewer to elicit a certain psychological response in him. We as participants in reality, have a long-ingrained lexicon of correlating rules- contextual links which have been made between certain visual signs, and what they represent. We have built up millions of neurological linkages between a visual cue, and a conceptual idea. It is how we navigate the world, by knowing this, is not that.

The phenomena is how our brain can tell the difference between a cat and a small dog. Both animals may share a size, a colour and even some habits, but we never mistake one species for the other. This is because the brain is built to develop a series of rules which describe ‘dog-ness’ to us , yet do not correlate to the rules of ‘cat-ness’. This phenomena is clearly shown when one observes a toddler learning to speak. That baby will often call things by wrong names, because the ‘rule’ is not established yet in the developing infant brain. There are still ambiguities in the rule for that child to come to terms with.

You as an adult can also experience this same phenomena of concept rule-developing , if you cold-turkey dive into a new discipline -something like mechanic work- without having any sort of background in it. You will immediately mix up the names of parts and tools which are ridiculously easy for a shop-savvy worker to discern. This is not because you are stupid, but because the terms of the ‘concept-rule’ which describes, for example, a solenoid has not been established yet for you. All you may be able to hold onto at first is the name, and some inconclusive traits such as its general location in the engine, it’s shape, or even it’s colour. You will soon find, these variables are not faultless descriptors of a solenoid as every brand yields slight variations in those generic qualities. Your concept-rule must become more elegant for you to fully grasp what a solenoid is.

The phenomena of conceptual rules which signal to our brain different qualities within the general category, also work up and down within the hierarchies of aspect. This produces in us, a more particular classifications such as ‘friendly dog’, or ‘sad dog’ or ‘strong dog’ or ‘vicious dog’. These conclusions develop cognitively, as a result of our tabulating/recognizing the predictable visual-cue aspects common between all dogs which enact viciousness or friendliness with us. The forming of such connections between visual clue and conceptual classification has been built-up meticulously in our consciousness over our own personal lives as well as over the millennia. This is how we have come to navigate the world. In our prehistoric past it was a matter of life and death if we were unable to tell the difference between the signs of viciousness and friendliness in animals.

What has this to do with figure drawing, you may be asking yourself? Establishing the idea of concept-rules may be the necessary groundwork needed for skeptical artists to accept this next drawing fact:

conceptual-rules also apply to the proportions of the figure

When we talk about proportion, what we are describing is the relationship between the constituent parts to the whole. In a figure drawing, this would describe how the arm length relates to the body length, or how the chest width relates to the hip width. Every possible relationship of one anatomical metric, to another is the domain of proportion.

As stated above, and within the opening, there are well established concept rules of body proportion concluded within us already. As we are viewers of reality, we know how to recognize a strong man from a weak man, or a fat man from a thin man. What Andrew Loomis sets out for us in the next section is the mathematical laws regarding proportion, working behind the conceptual rules already concluded within our brains.

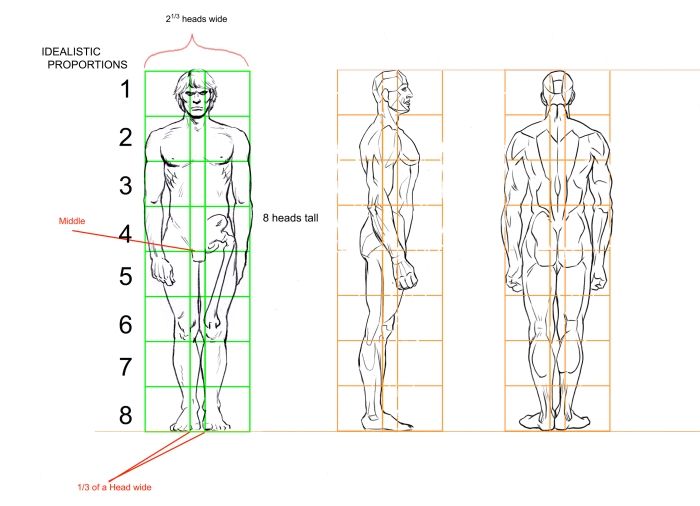

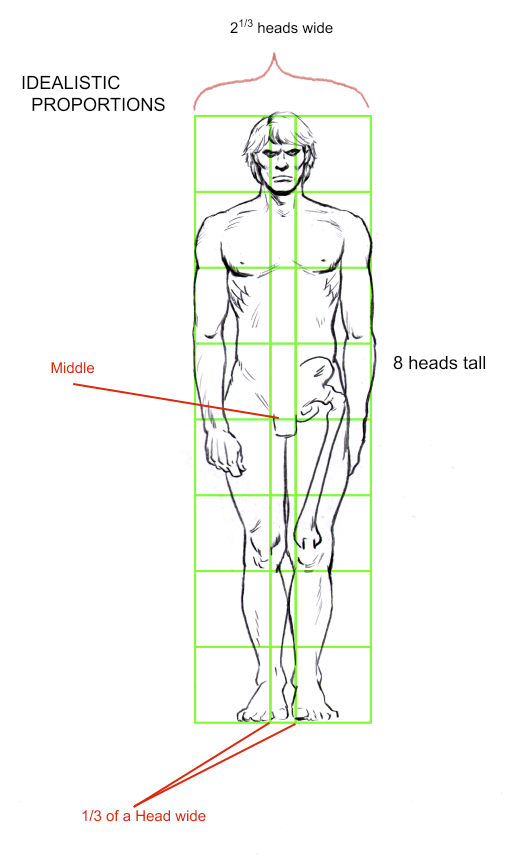

There are several proportion-based concept rules which describe different qualities in the human figure. For now, we will establish only the first of these. This is what is called Idealized Proportion. This proportional rule, applied to the human anatomy is a rectangle, divided into 8 equal divisions, each being commensurate in height (but not in width) to the figure’s head. We use the head as the unit of measure because it is the simplest and most convenient unit. The head may have other elements such as a beard or ample hair, extra fat etc. so for the sake of clarity, I will declare here that Loomis means the skull with all the musculature upon it as the unit. Do not count extra mass from tissue or hair as part of the divisional unit.

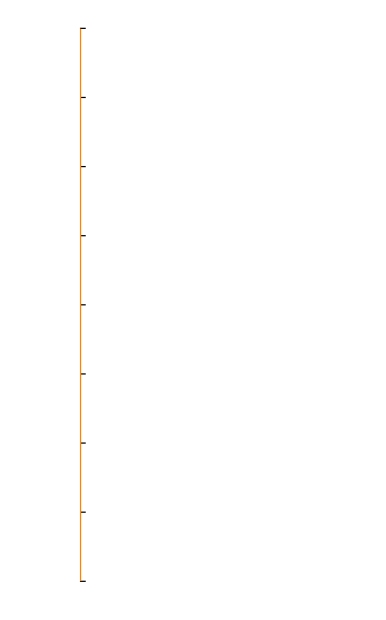

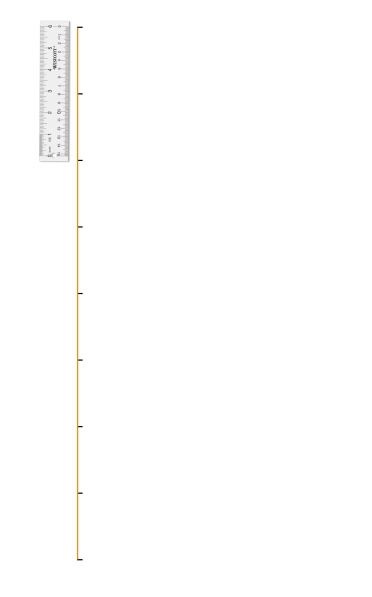

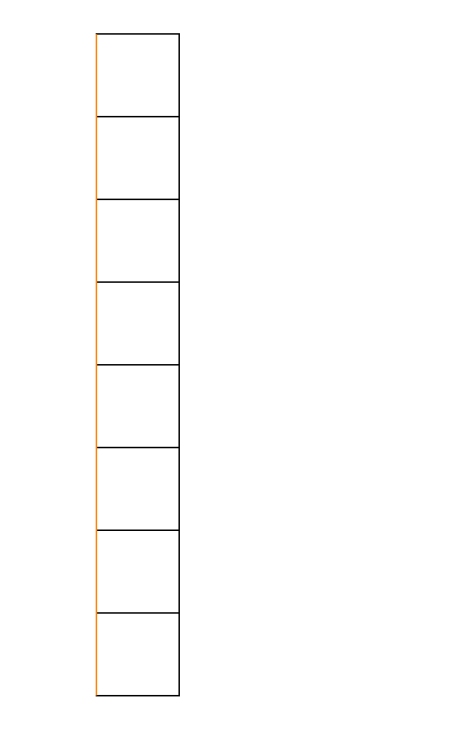

For your exercise today, take any desired height which suits your paper, and represent it with a vertical line. Divide this line into 8 equal sections.

Measure the distance from the tip of your vertical line to where the first mark crosses it.

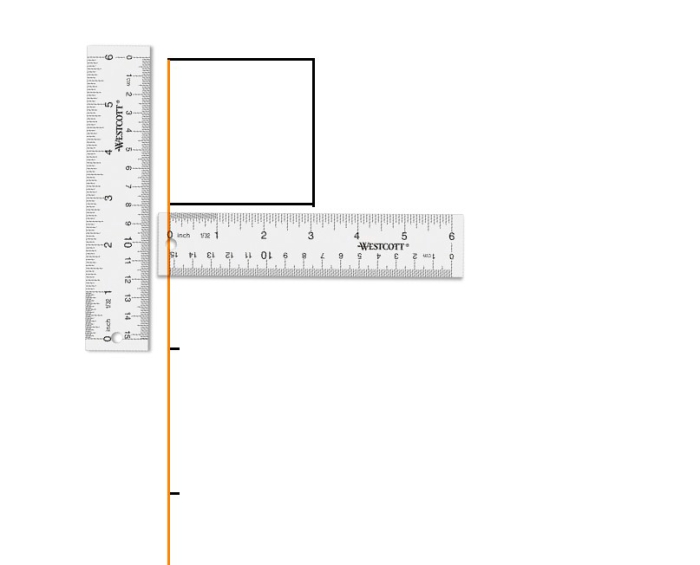

Make a perfect square at this point. Make certain you use a right triangle to draw the section markers at a 90 degree angle from your first line.

Fill out the remainder of your vertical line this way, repeating the perfect square for each point.

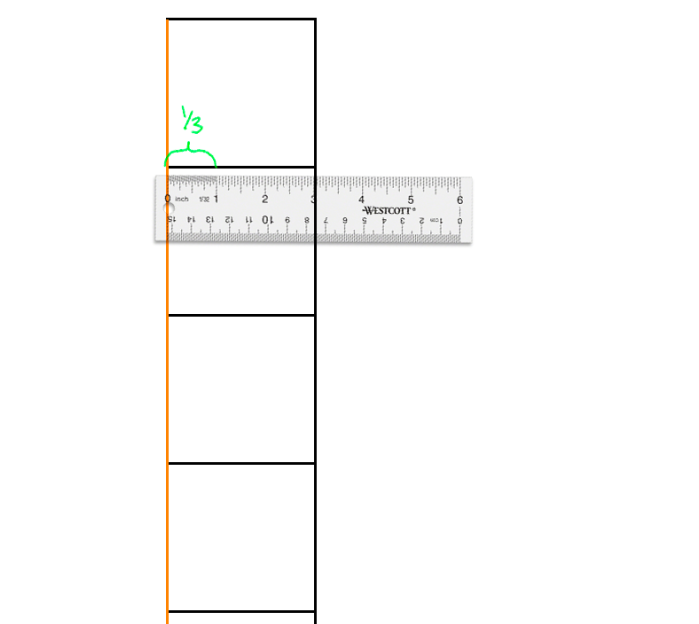

These squares represent the size of your figure’s head. This layout will tell you the height of the figure, and where to place the anatomical points, but we need more data to determine the proper width of your Idealized Figure. To find the width, determine the measurement of 1/3 the unit which make up any of your perfect square’s dimensions. In this case, 1/3 of my dimension happens to be 1 inch.

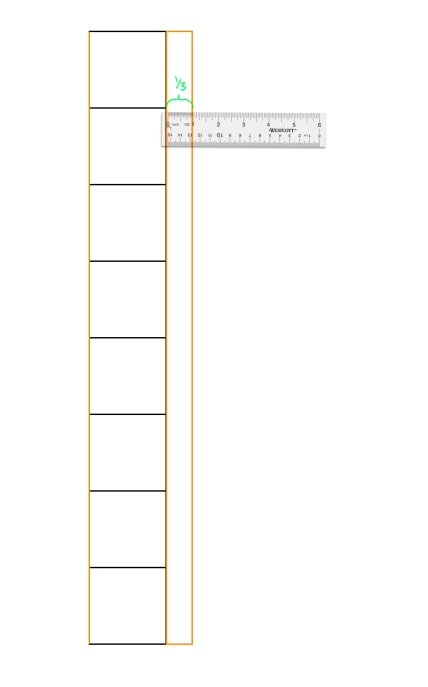

Recreate this measurement adjacent to one of the sides of your layout. This will be the centre 1/7th of your overall layout rectangle

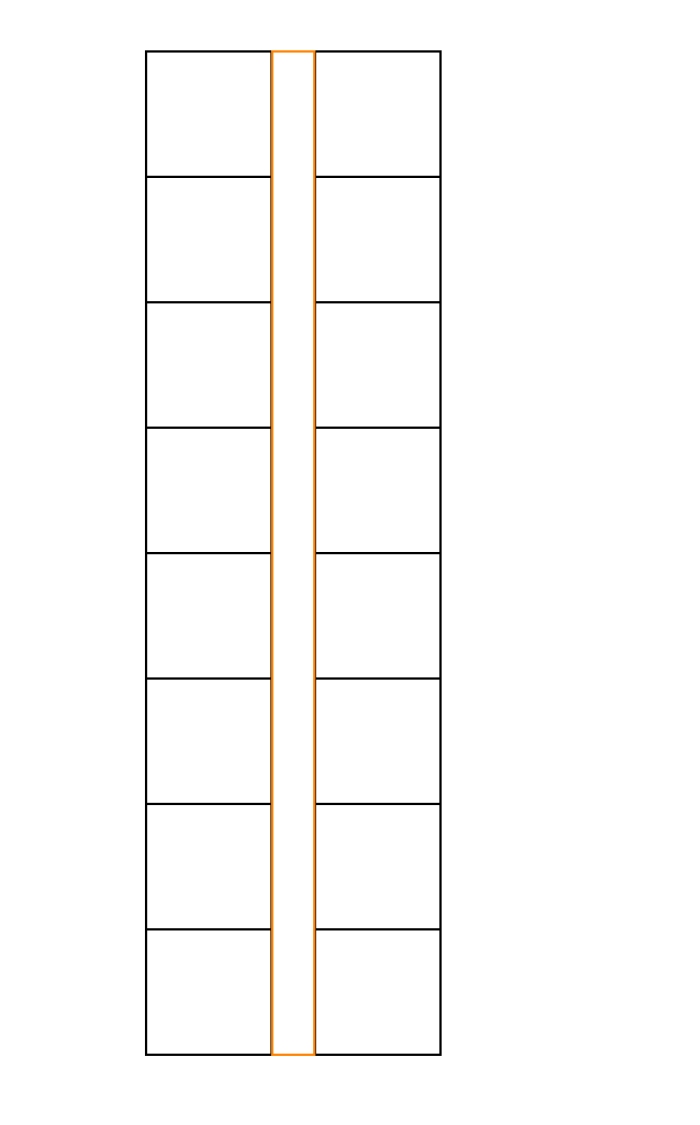

Finally duplicate the original 8 squares on the free side of the 1/3 spacer (in orange here) which you just made.

This rectangle will show the Idealistic Proportions both height and width for the human figure. Draw your figure in this frame after my drawing, but it is not necessary to render the anatomy correctly.

What is most important is that you begin your cognitive journey establishing this relationship as a conceptual rule. I have repeated this process so many times, I can set-up the relationship of Idealistic Proportion on an invented figure, without relying on the measured mechanical divisions. Furthermore, I can see instantly when another artist does not know this rule, and presents figures which do not meet this proportional standard. This will happen for you as well, but not unless you execute the drawing reps of setting up the frame, and fitting the figure standing within it. Learn to hit the appropriate places where the anatomy lines up with the division lines. Here are some sign-posts:

- the space between the nipples is one head’s width

- the waist is a little wider than one head unit

- the wrist drops just below the crotch

- the elbows are about on a line with the navel

- the knees are just above the lower quarter of the figure

- the shoulders are 1/6th of the way down

This is a matter of training your eye to see the proportions. Many consumers of art, and fans are impressed with design and style in a drawing. They express their adoration for meticulous rendering or verisimilitude. These fans are indiscriminate to the set-up of the fundamental proportions of the figure because their eyes have not been not opened. When they lavish accolades over a finessed figure drawing, which is not set-up properly proportionately, it is like praising meat masked with excesses of salt to baffle the recognition that it has actually gone rancid.

Things are good and right when they are consistent up and down its own hierarchies, like a properly built house. Such a work is efficacious through its fundamentals, its structure, its details and finishing. To understand Figure Drawing For All It’s Worth, we as artists will do well to start with integrity at the fundamental stage of proportion.

Next week I will show you the female figure, as well as some other standard proportions. This will help you understand why the natural proportions found in day-to-day life are not acceptable in an illustration, and how more extreme proportions may be suitable for certain applications in figure drawing. Thank you for reading!

This is a lot useful, thank you as always! Maybe it’s just my impression, but the lesson made me realize that many artists, even if they know the Idealized Proportion, mess up with the width of shoulders and hips.

P.S.: I was busy and didn’t manage to give proper feedback on lesson 6 and 7, I’m going to do it as soon as possible. Also, I think I’m going to comment on your blog rather than on Twitter for the rest of the lessons.

LikeLike

I totally agree with you. The distortion in hip to shoulder ratio always happens! Thanks so much for taking the time to comment. I’m glad you find it useful!

LikeLiked by 1 person