This next section of Understanding Loomis will begin to address the essential question of how an artist can create realistic shadows when a subject matter is not a regular geometric shape, for instance such as in the case of a woman’s face.

Loomis begins his answer to this important question with a short word regarding theory. He starts with the observation that laypeople cannot tell the difference between talent and knowledge. He means that when most folks perceive a person of skill executing his craft – be it drawing or drywall- the product may seem like the result of an immaterial gift, rather than the exercising of an integrated, practiced knowledge base. This is a mainstay of fine-art, where the ‘myth of talent’ seeks to delineate a line between craft and art. The position being held by the talent advocates states that artists are geniuses, and their work is akin to revelation. These elect few ‘geniuses’ are not craftsmen, but vehicles of expression who’s concepts (opinions and ideas) are purportedly the seat of their greatness. Loomis being an illustrator reveals this as a myth with the straight-forward observation that talent really is a mis-appellation applied to what really is a practiced craft. This confusion and elevation of the discipline into the realms of fine-art is done by those who lack knowledge of the pursuit, onto those who have knowledge of that pursuit; that is the ability to draw and paint.

Loomis defends the position that drawing and painting well, is a matter of understanding the terms of how such a skill is done and that there are specific areas of technical knowledge needed in order to manifest the illusion of reality on a 2-d surface.

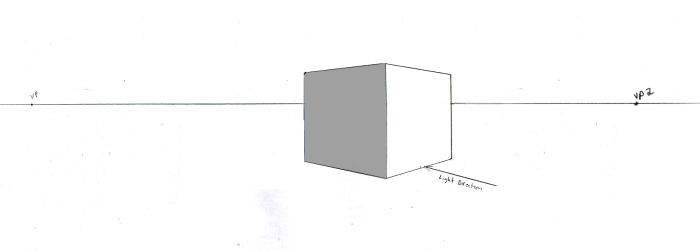

Now he goes into the nuts-and-bolts of shadows and complex forms. Loomis begins this section by indicating that when a drawing or painting is being done, and a smooth tone is chosen to be interrupted by the artist, there are only two ways an observer can interpret that change in tone.

- That the change in tone represents a change in the character of the surface which is trying to be represented (say for instance, a few small rocks on a wide stretch of beach)

OR

- That the change in tone is a smudge on the surface of the art, and not part of the image which is trying to be represented.

The interpretation of a dark tone as being a change in surface character within the picture, vs it being some sort of surface smudge is exclusively within the domain of the placement of that mark. A properly placed, grey mid-tone mark, will read as perfect sfumato of light on a woman’s cheek, where a misplacement of that same mark by a matter of degrees will make it now appear as a dirty spot; a mistake where your hand disturbed the charcoal.

This is a very useful distinction to keep in one’s mind when making a picture, in that many artists are compelled to ‘fill-in’ areas with various marks and tones. The naive illustrator overly relies on hatching and details because he does not know where the exact place surface changes should naturally occur given the object and the light he is attempting to draw.

Unfortunately, many naive approaches in art can be interpreted as elements of style, and therefore also intentional on the part of the artist. This conclusion is generally false, and such art is really most often the product of the artist trying to ‘fill in’ the work. People usually have a good enough eye to see that something is wrong in a picture (see earlier posts on intelligent observation), but they lack the knowledge of why. When this happens to an artist regarding his own work, the common natural response is to fuss over the area, adding random marks and tones in order to address the error in intelligent observation the artist is experiencing. For instance, Loomis indicates elsewhere that the appearance of a receded or distended jawline in a portrait, which causes the artist to keep refining the contour of the face, is most often nothing wrong with the jaw, but actually the effect of the artist having misplaced his subject’s features, such as a too-low mouth, or too-wide eyes.

Naive art is often given a pass, and even loved by consumers and the audience in some cases. Whether intense, ‘stylized’, ultra-detailed and highly-rendered art is your cup-of-tea or not does not change the fact that there is a particular place where surface character changes in regard to light, and knowing those particulars is better than not knowing.

Drawing is only difficult to those who don’t know what information to hold onto when representing a subject. The placement of contours and changes in the nature of surface character are measurements and nothing else. When one knows how to measure these properly, the matter of placing them is made simple.

Knowledge over talent. Know how to do it, don’t try to guess because you can’t.

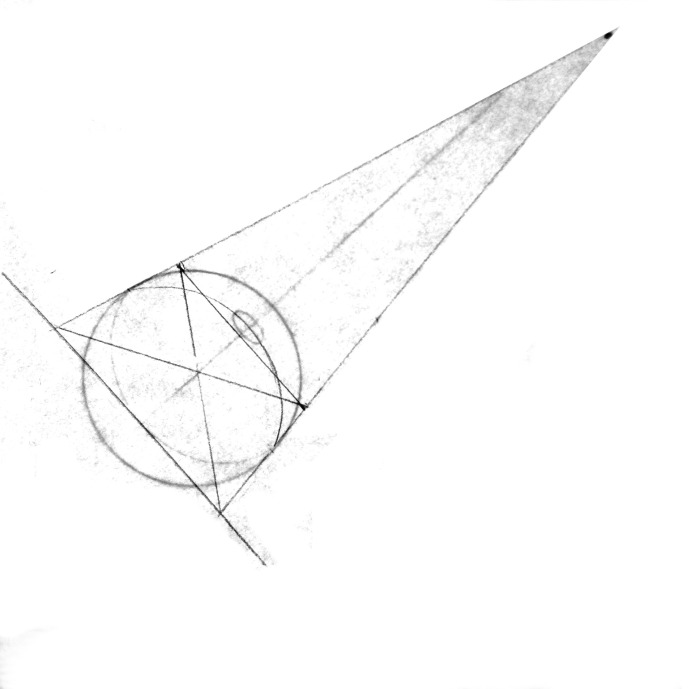

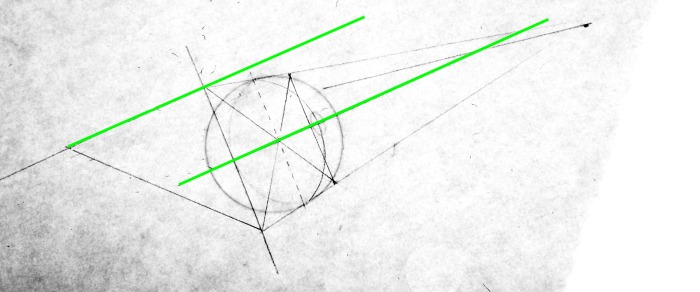

Moving on, Andrew Loomis declares that to find the planes of an object is to watch the angle of the surface as it changes, then record the tone or value caused by the angle. I think this is most easy to understand when put in the context of drawing a face. Loomis wants us to recognize that areas of light on form, always fall into a shape. So do the dark tones and the half tones. To be able to represent a face in light is to know these shapes, and place them together properly.

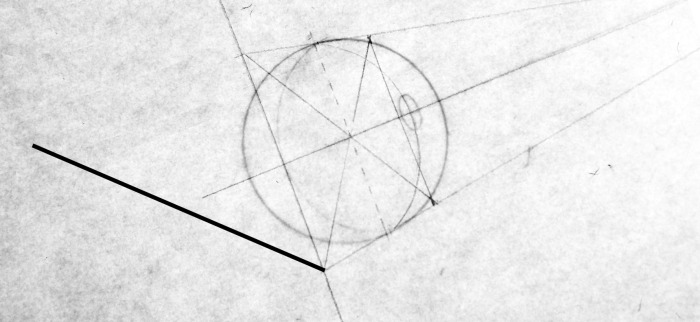

Consider this drawing I have done, presented below:

A face is drawn as any other surface by following the angles of the surface and with each change of plane, noting the change of value. Highlights are found on the highest parts of the form, and nearest point of the surface to the light. As you can see in the image above, there is no need for complicated and intense detail. The value of the shadow tones are limited to only 2 in my picture; full black for shadow, medium grey for half tones. The brightest parts of the face are represented by no pencil work- it is the paper colour. Squint your eyes at my drawing and you will see a generalization of the values, and recognize that the mid-tone is basically uniform. With the magic of photoshop, I reduced my image to only 2 tones and the white ground. You can still read this as an attractive woman’s face. This is because the placement of the shadow tones is correct . We read this as a face, and even an attractive face because the marks are in the correct areas. If they were moved about, the image would become less attractive.

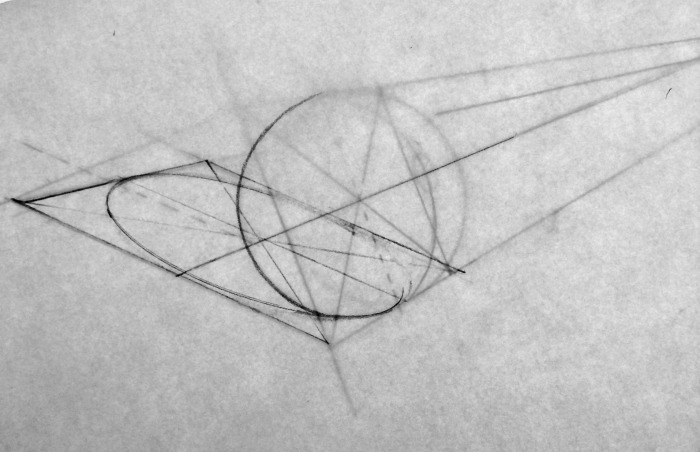

Here I have taken the shapes of value, and moved them around a bit, then added a red filter to indicate the distortion. This example shows how the positioning of the value-tones is the essential variable which artists need to get correct. The actual ‘prettiness’ of the particular eye or nose drawn is not what makes a woman’s face look attractive. It is the knowledge of how form creates shadow, and the proper measurement of where the artist chooses to place those values.

You can see in the red version, the masses of tone when slightly moved, also move in our interpretation of them from descriptions of value to random marks. The tones appear like surface blemishes. Look for instance in the halftone mark which describes the edge of the woman’s cheek where it meets the muzzle of the face. The correctly placed one looks just like a shadow, the incorrect one is an unreadable mark -a smudge.

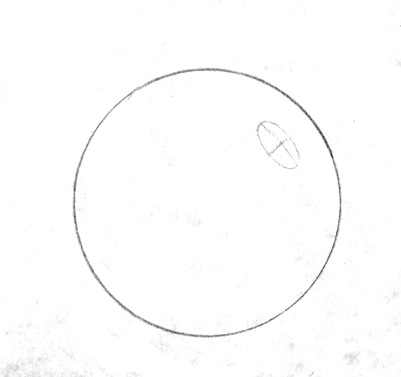

The obvious next question is how does one learn these various shapes, which represent light on form in regards to the multiplicity of facial angle and quality of light? The answer will be outlined in the next posting, which will go into the principle that light on form is related to the basic, and memorizable way that light falls on the sphere and the cylinder.

We will discuss this next monday. I hope you join me.

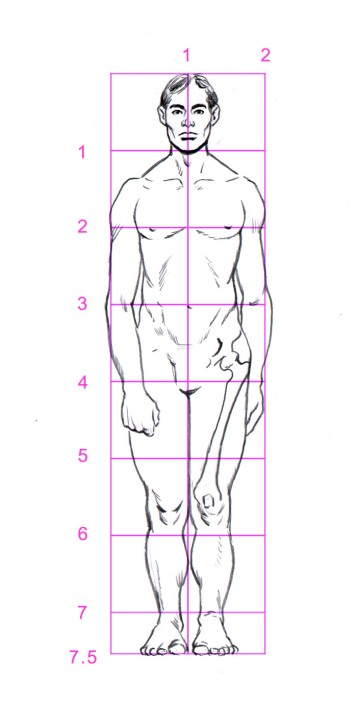

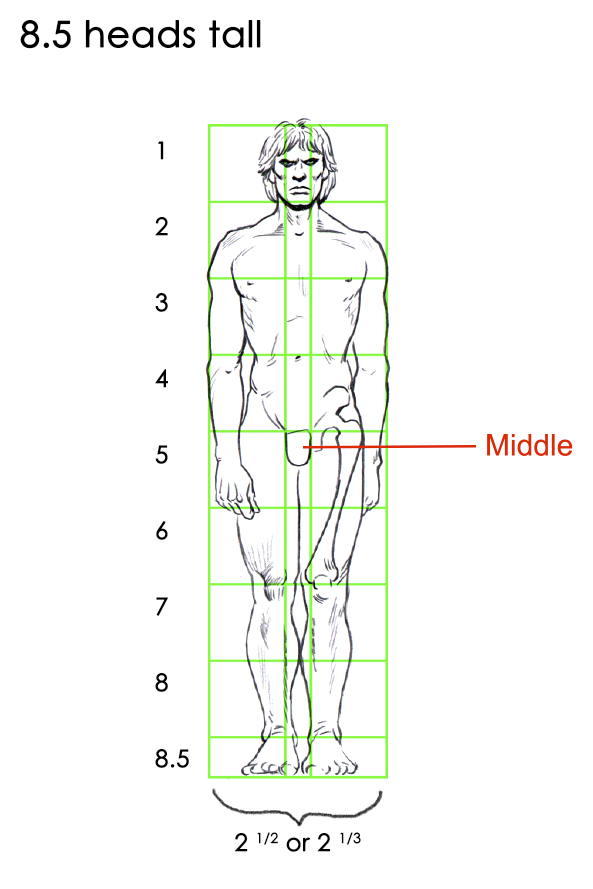

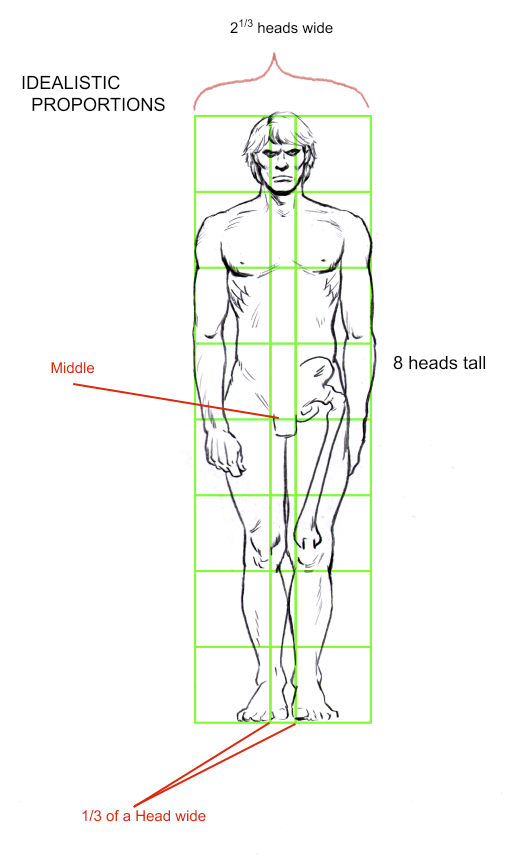

Most viewers who compare these proportions to the ‘naturalistic’ measurements used in the last posting will easily recognize how much more attractive the Idealistic Proportions appear to the eye. That being said, this proportional measurement of 8 heads is not the final word on Establishing a Key Figure. 8 heads is only appropriate in some situations when drawing the human figure.

Most viewers who compare these proportions to the ‘naturalistic’ measurements used in the last posting will easily recognize how much more attractive the Idealistic Proportions appear to the eye. That being said, this proportional measurement of 8 heads is not the final word on Establishing a Key Figure. 8 heads is only appropriate in some situations when drawing the human figure.