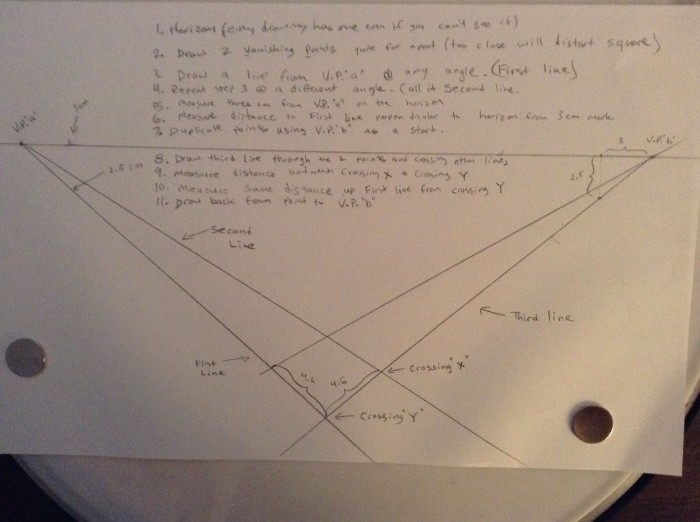

On page 43 of Successful Drawing, Andrew Loomis shows a very useful mechanic for artists to know in order to convincingly draw architectural details or features on mechanical objects in perspective. This example demonstrates how to project a sequence of repeating sections, found within a whole, using a vertical and a horizontal scale. This is similar to previous lessons, but it expands the skill set so that the artist can draw repeating sections which are varied in sequence. For example, imagine a condominium building in perspective. The viewer can see the front of the building going off down the block. This viewed side features a set of 4 windows, followed by a portico with a double entryway in the middle, then another set of 4 windows. Each of the openings of the windows need to be identical in size; but naturally, of a different dimension than the portico, which again is different than the two sets of double doors within. This then is an example of Variable Perspective Space, Within a Single Block.

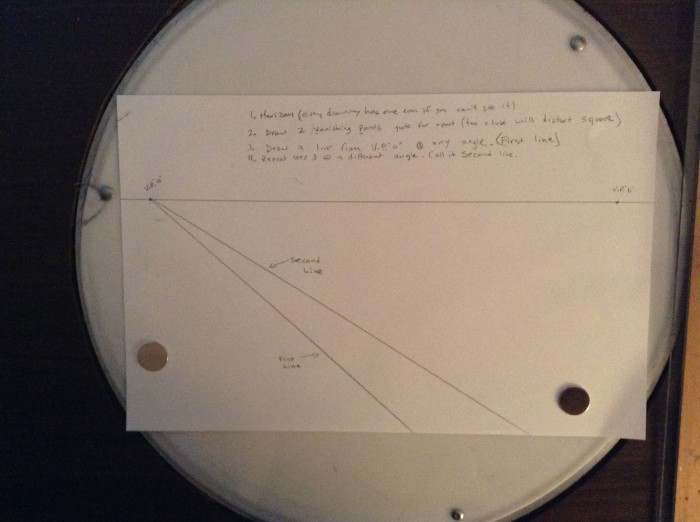

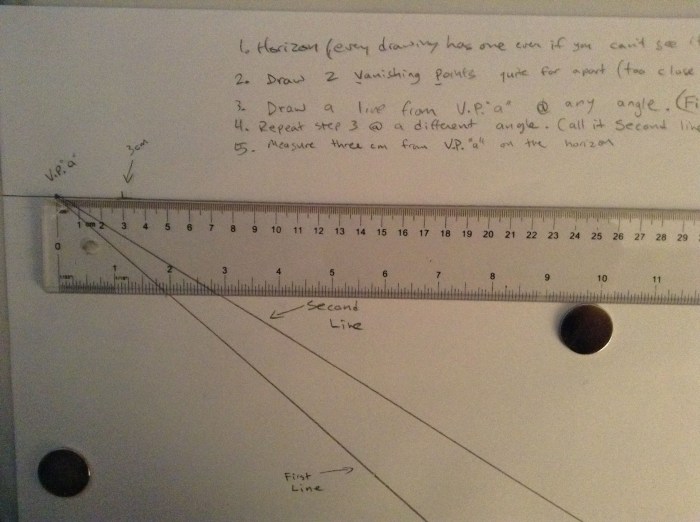

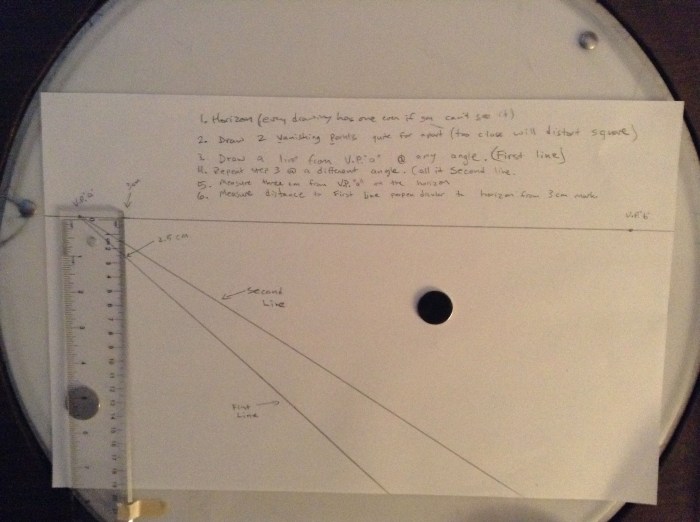

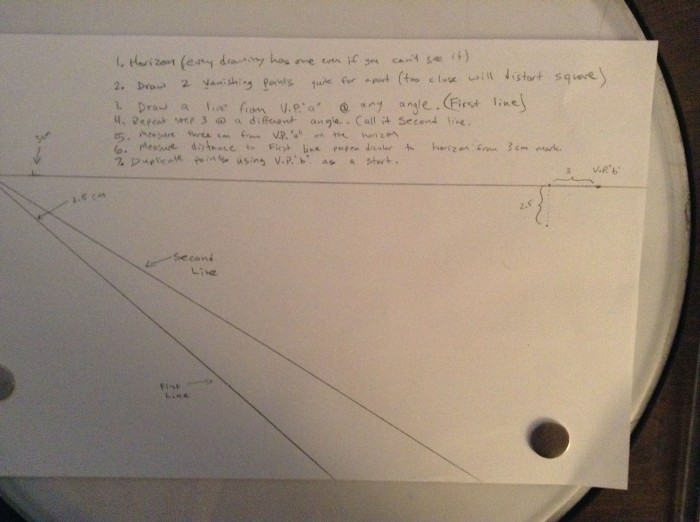

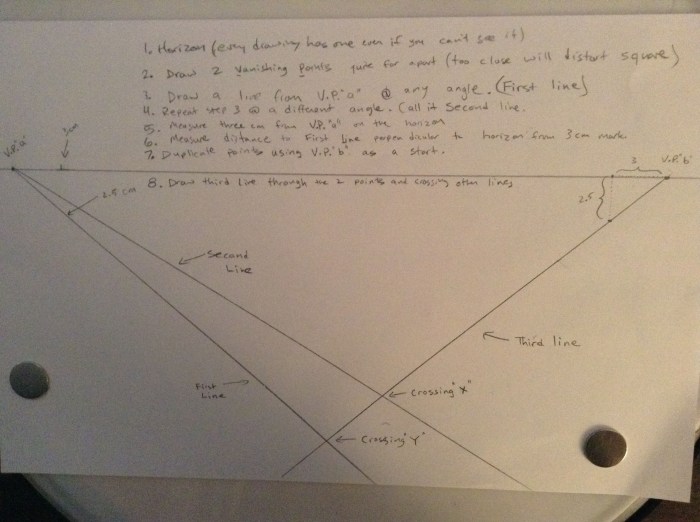

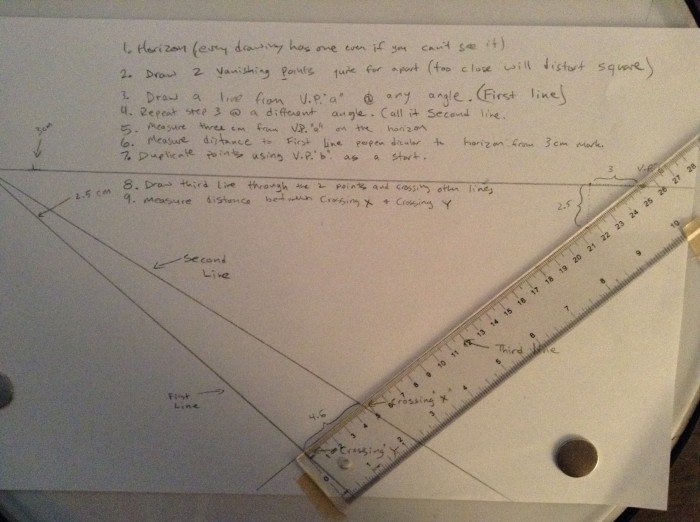

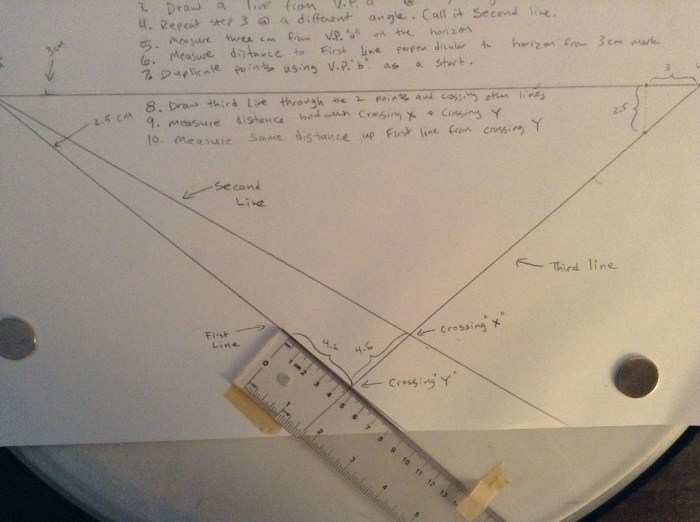

Let us begin.

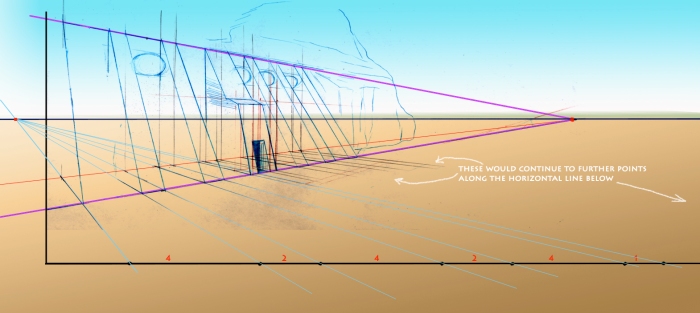

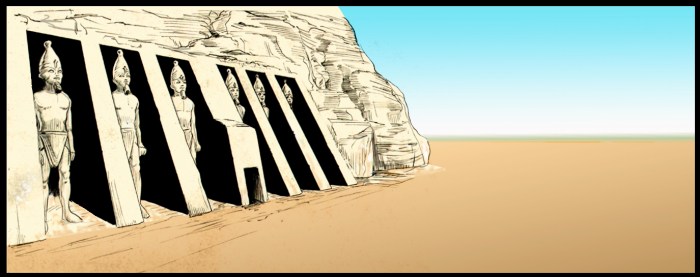

Suppose you are an illustrator, and you are asked to draw the Egyptian temples at Abu Simbel. Let us say that you are drawing the small temple, and you have (for whatever reason) a restriction as to the perspective you must use. You search through the internet for reference, and let us say that there is nothing in the correct perspective which you need. Short of traveling to Nubia, you cannot get a reference shot of the correct perspective. This is how it is done.

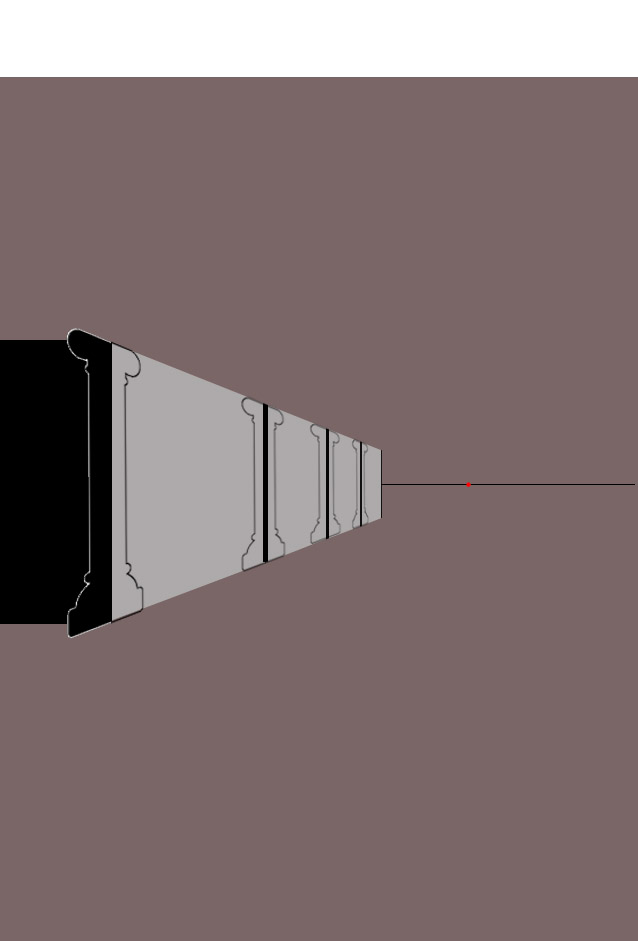

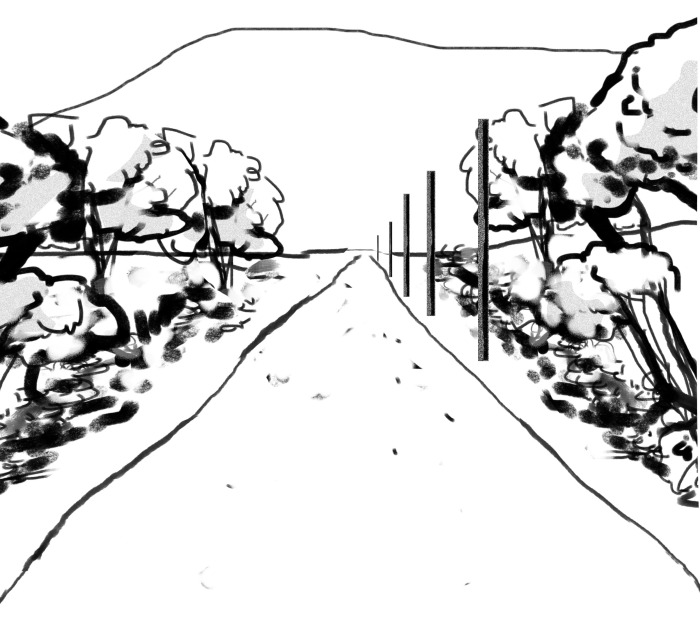

Here is the small temple at Abu Simbel

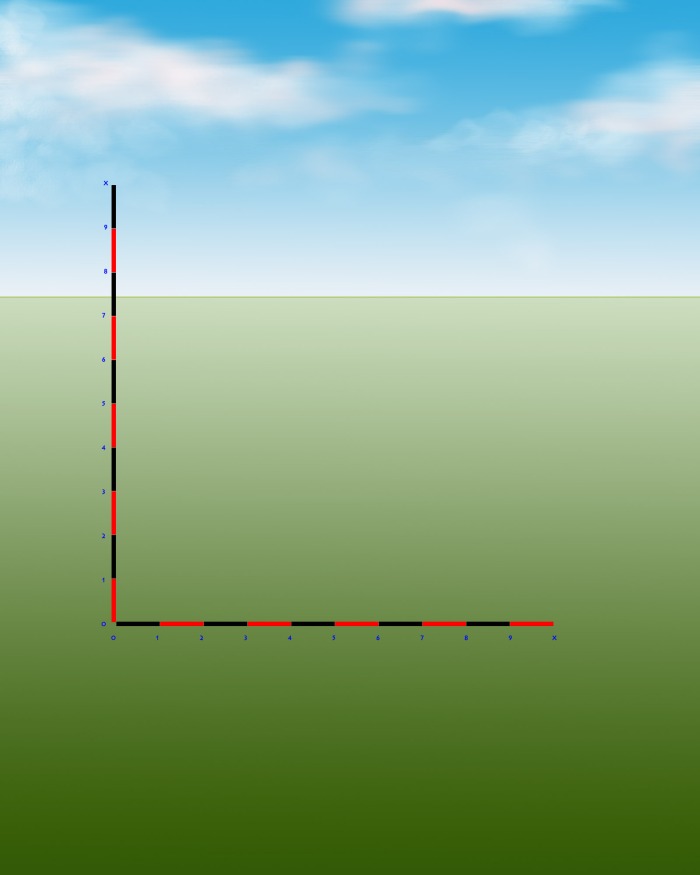

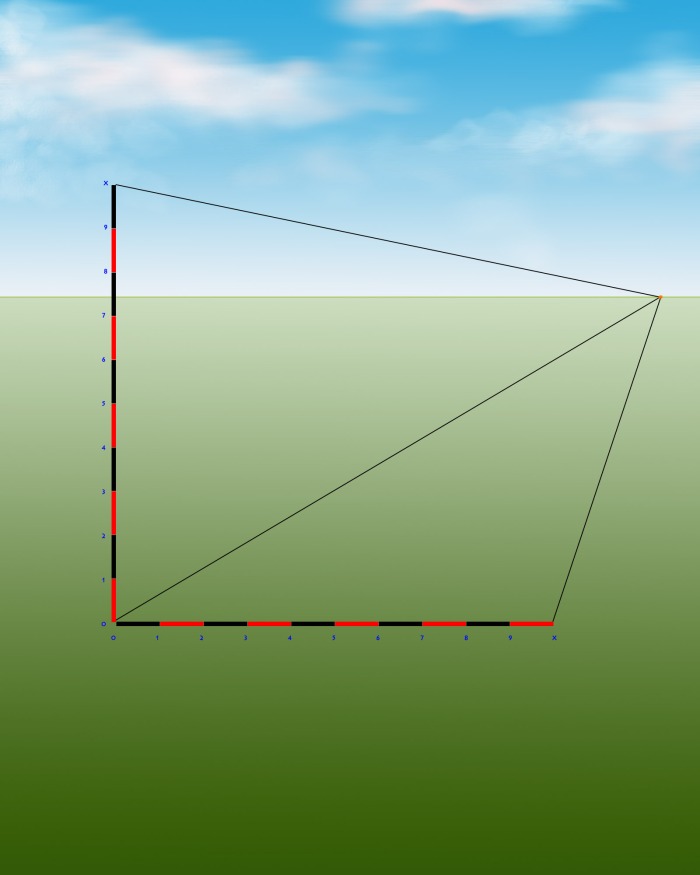

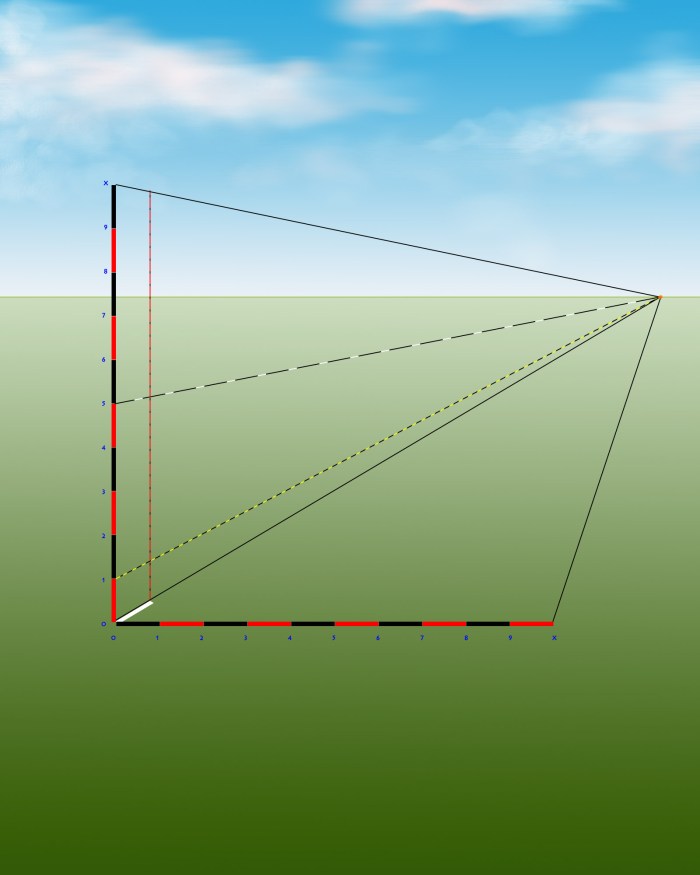

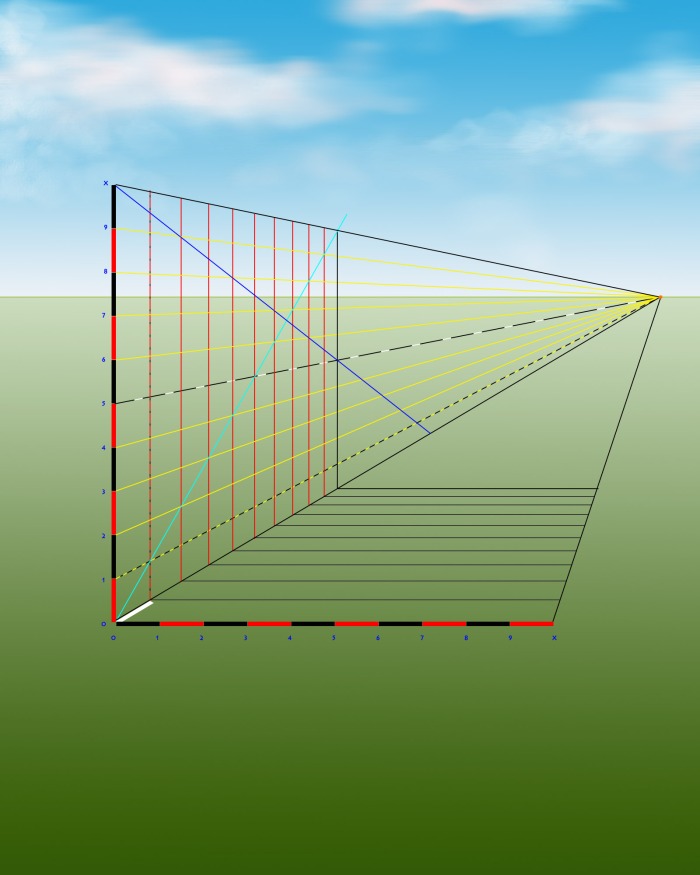

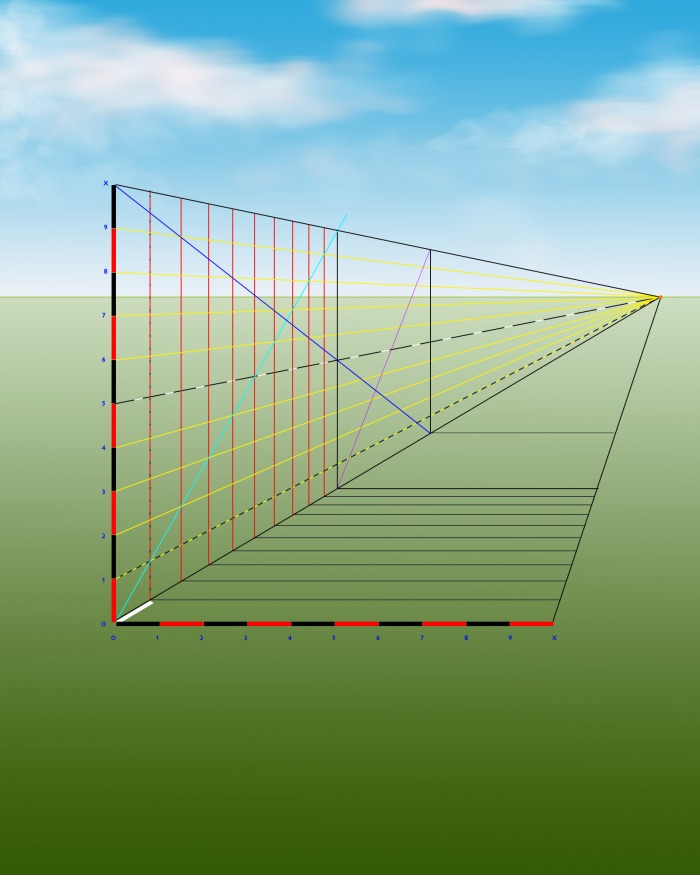

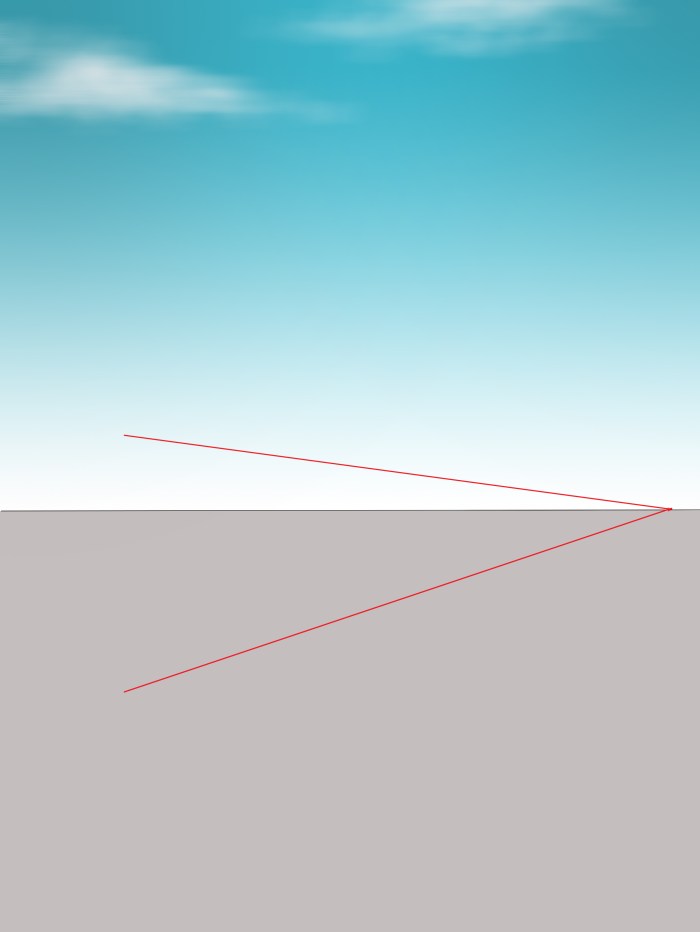

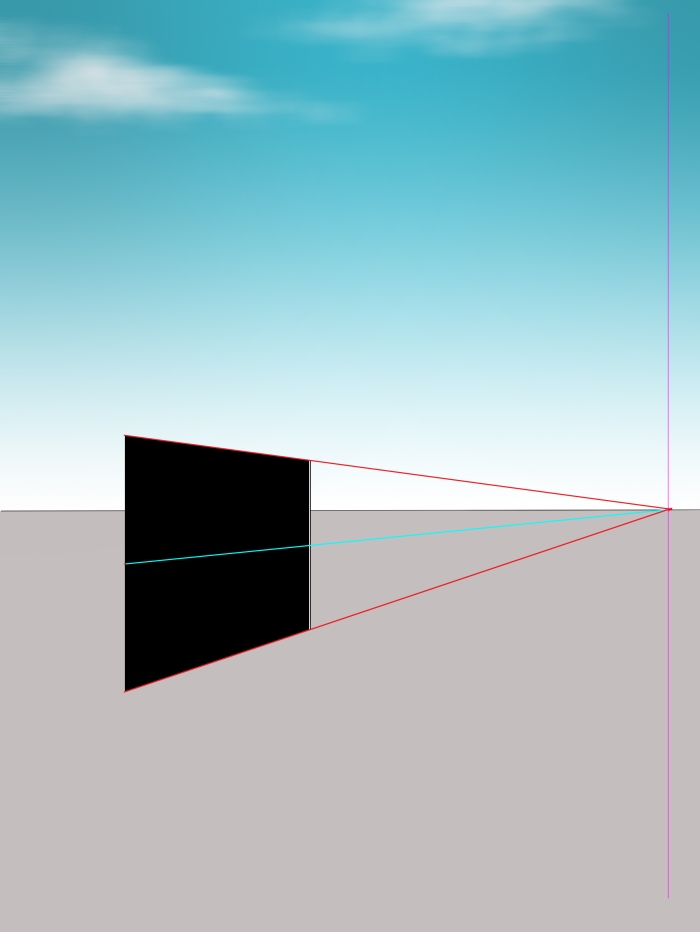

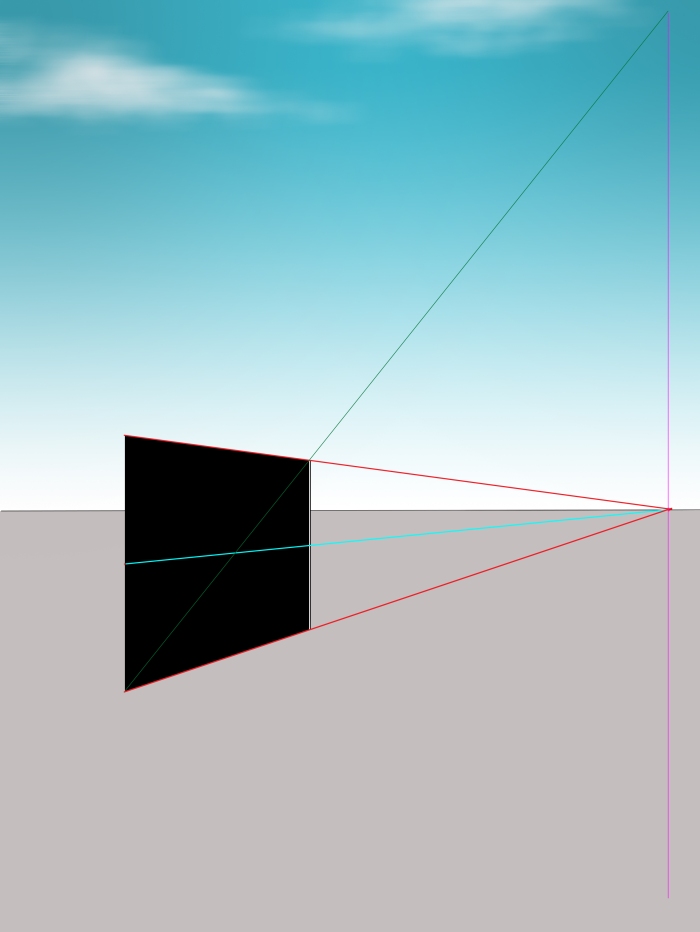

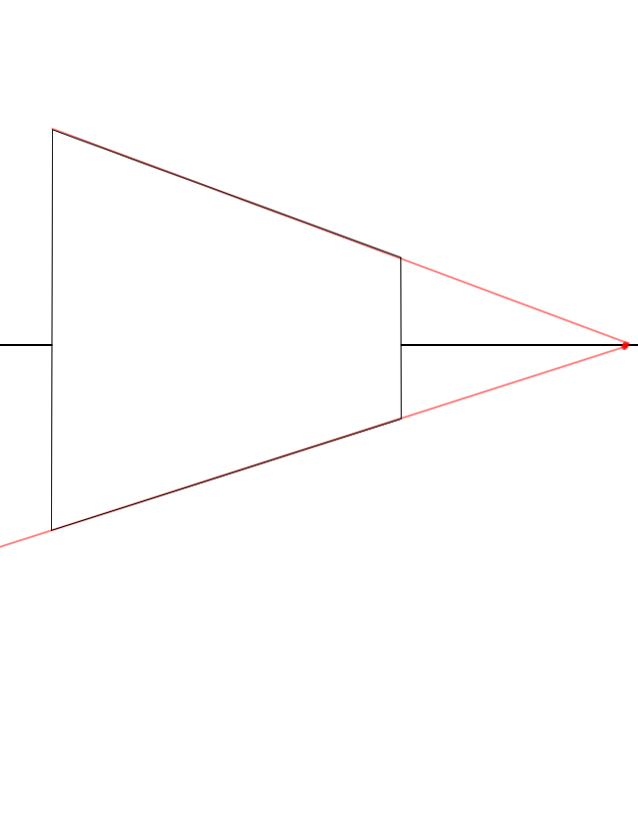

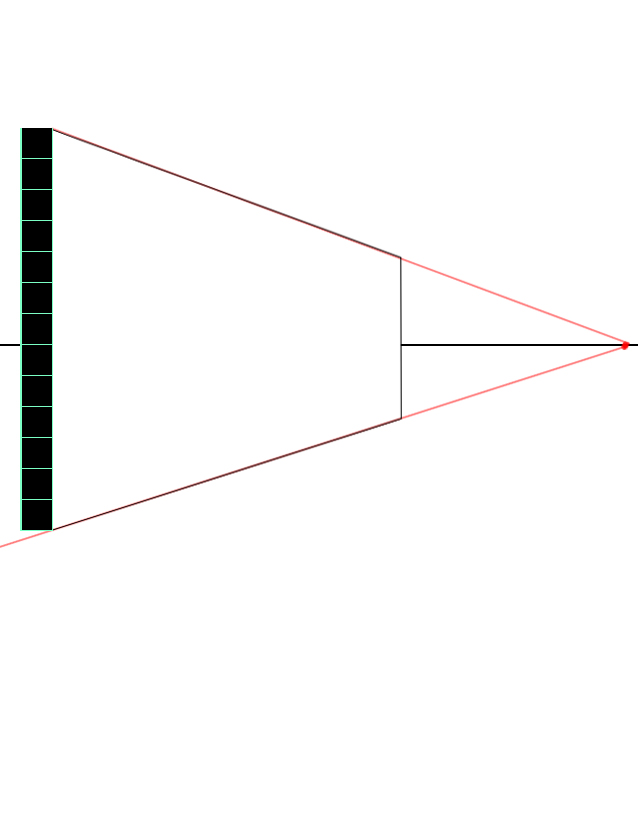

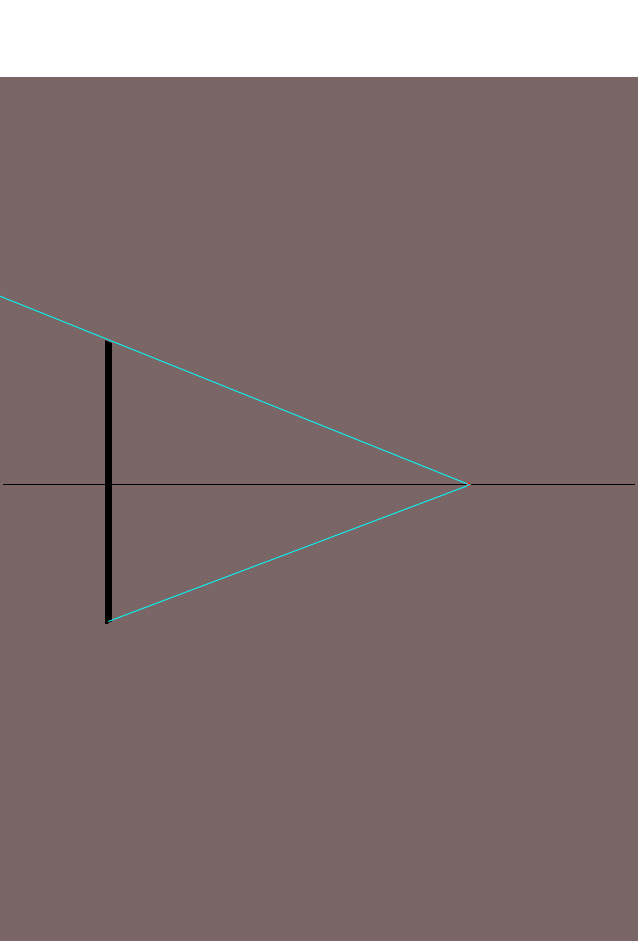

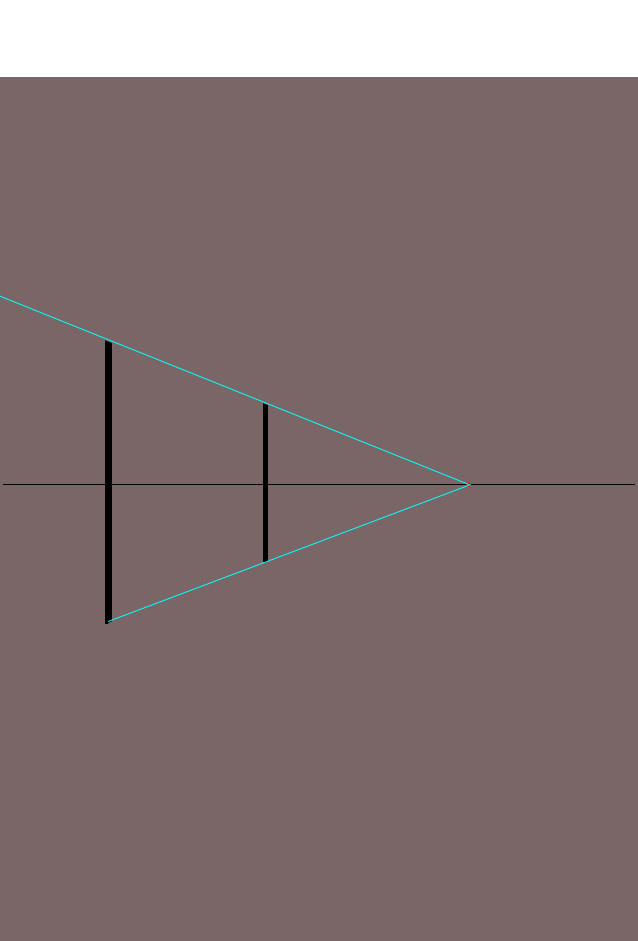

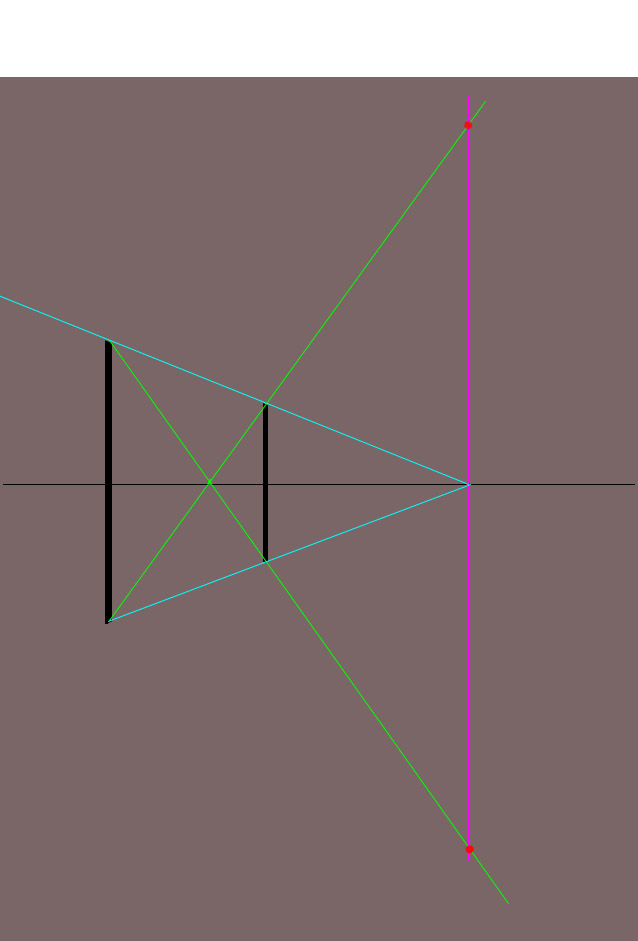

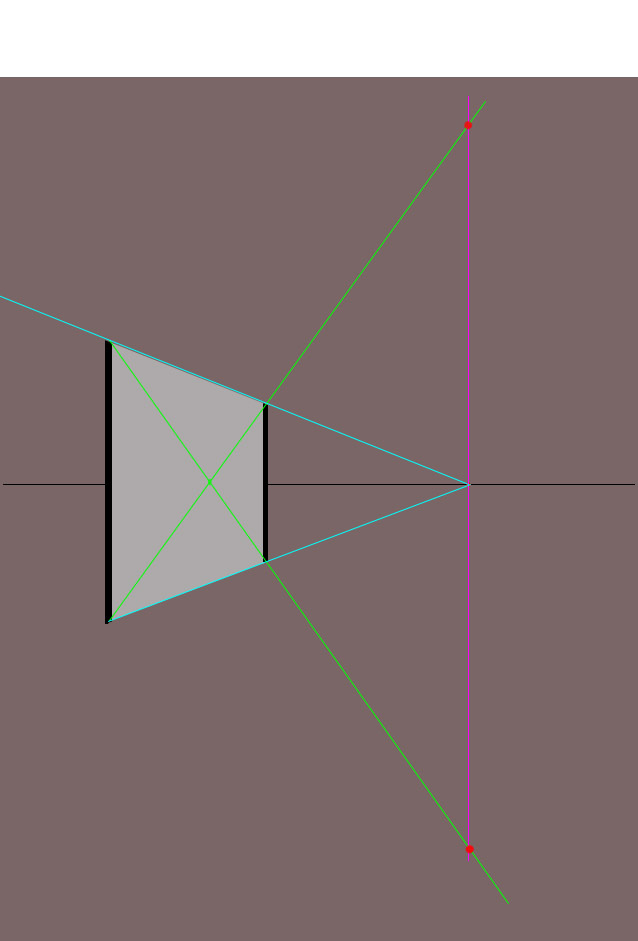

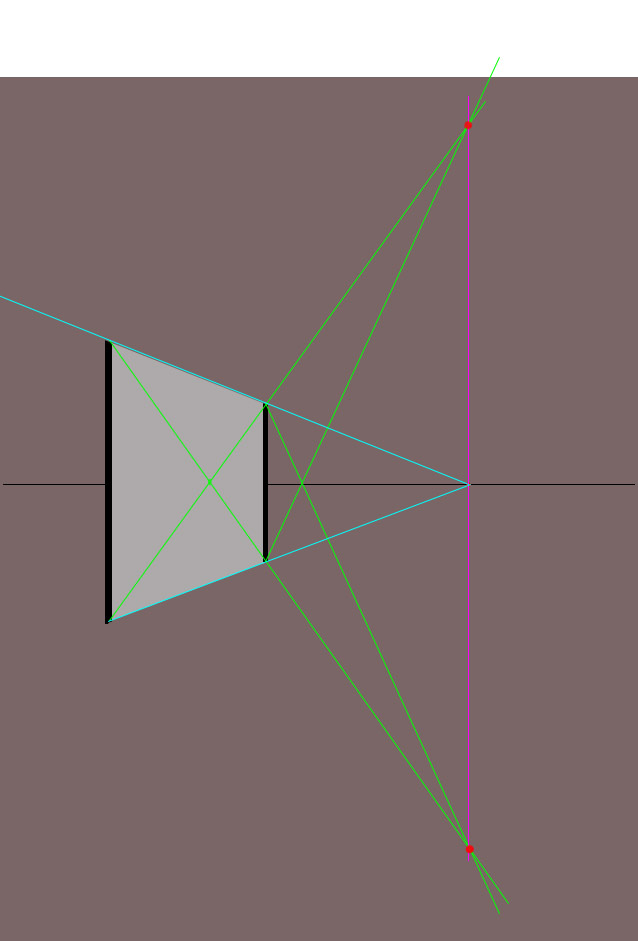

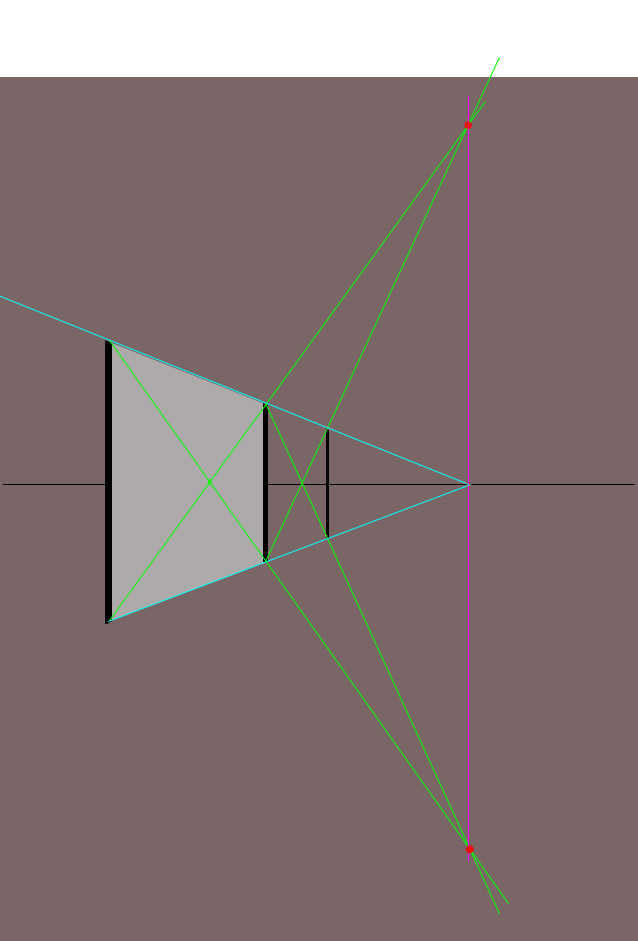

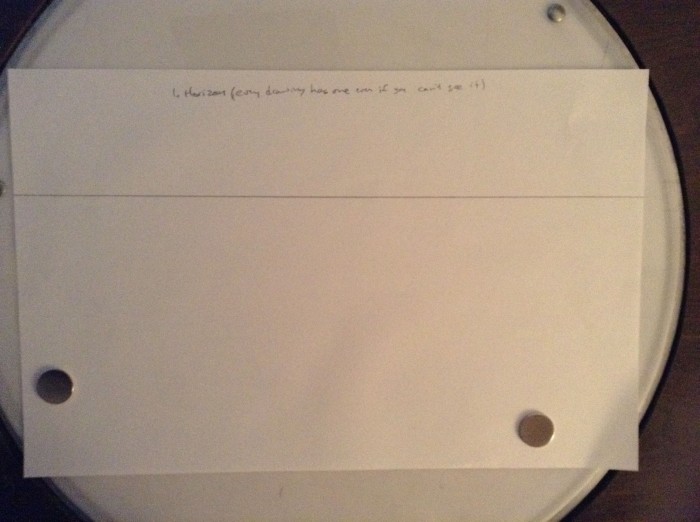

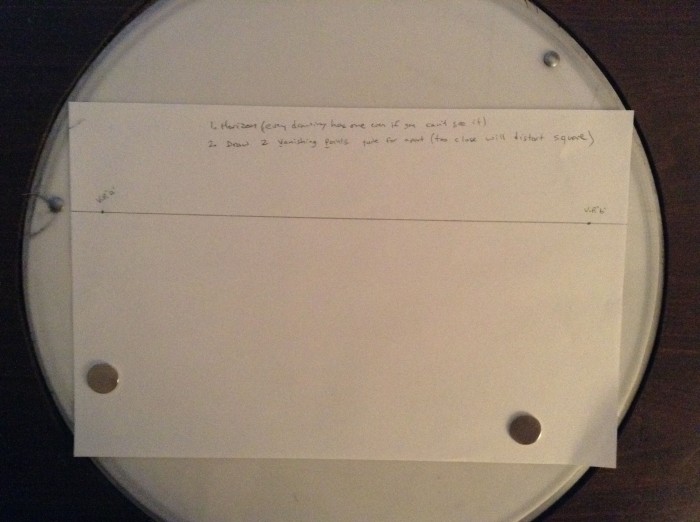

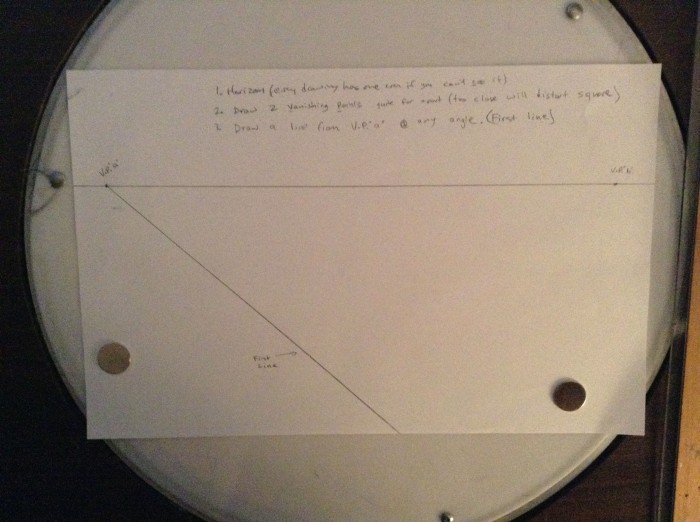

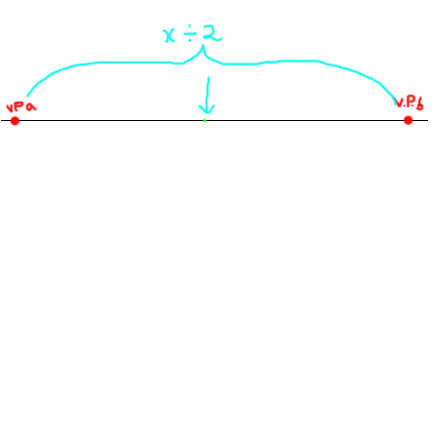

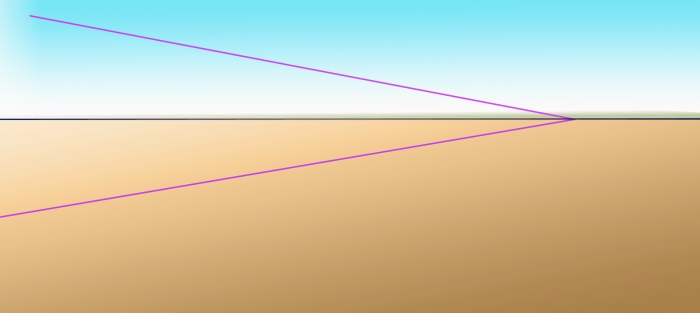

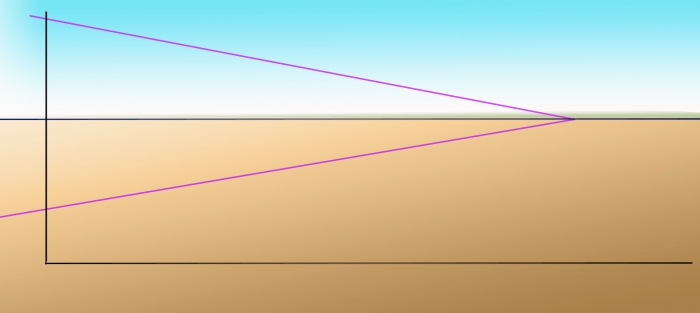

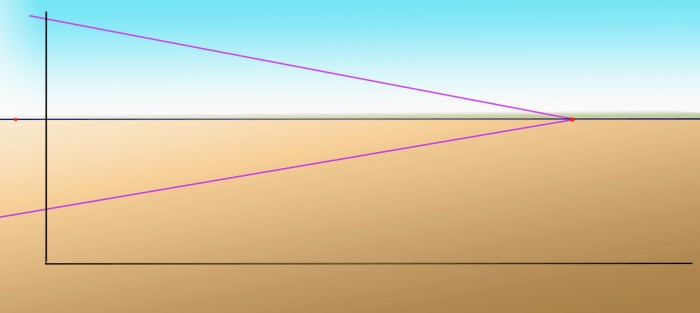

- Lay out the image in the angle you want, establishing the horizon and the perspective which you need to draw the site at. This can be done with any angle of perspective that you wish.

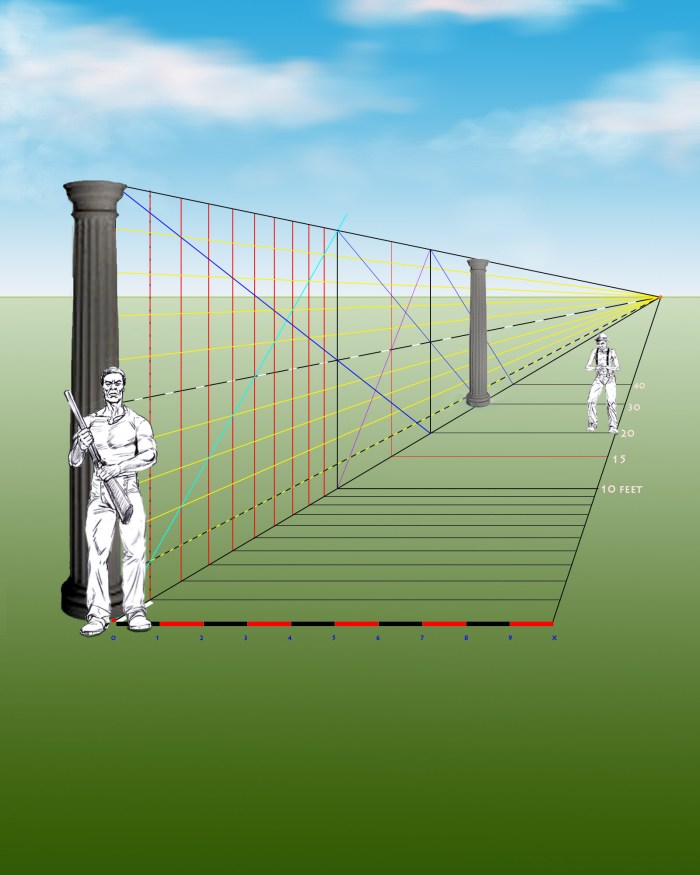

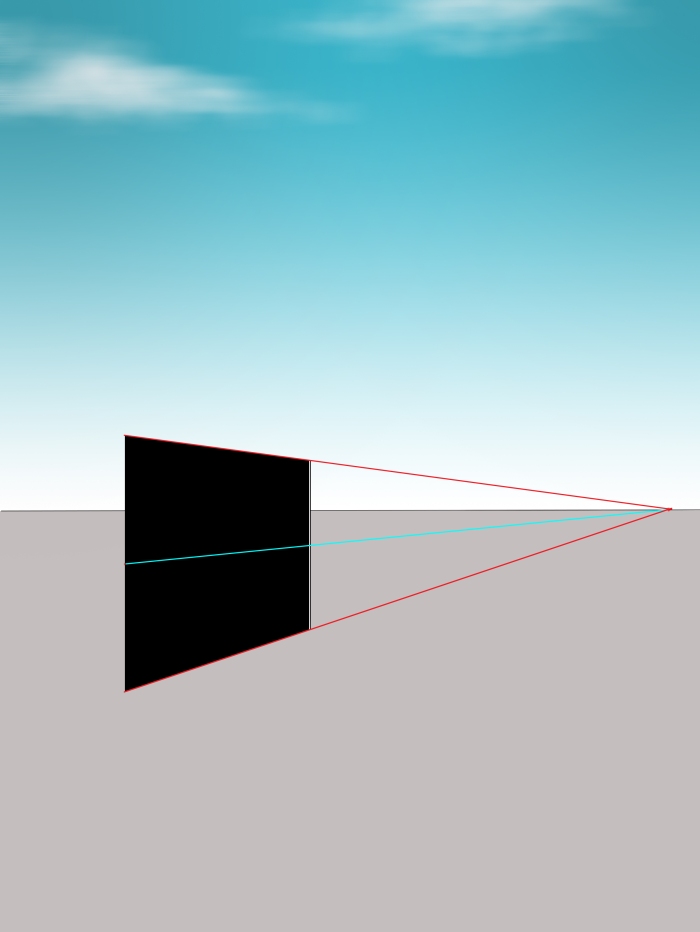

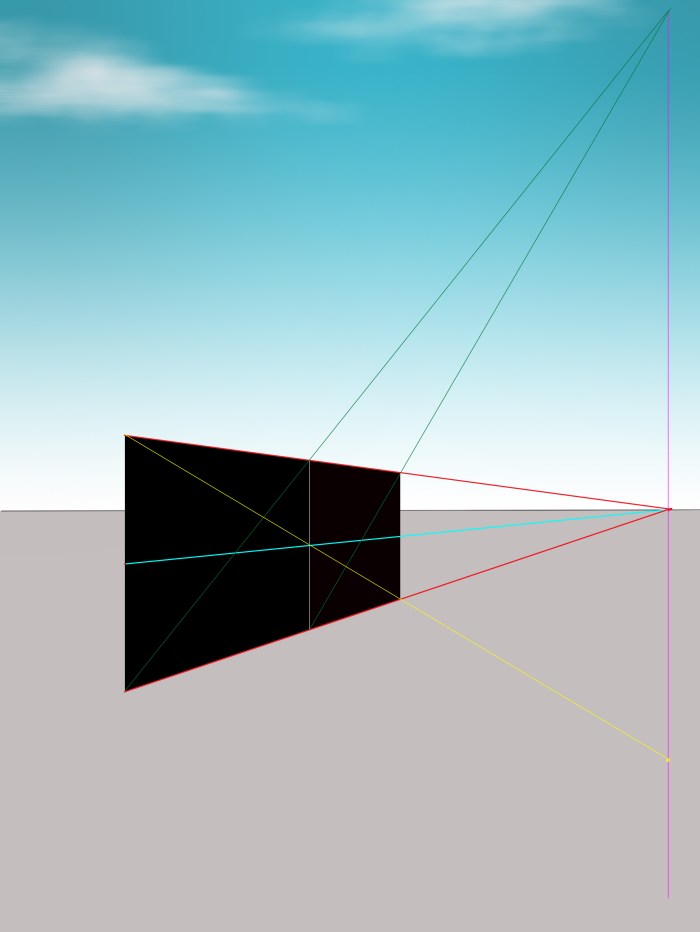

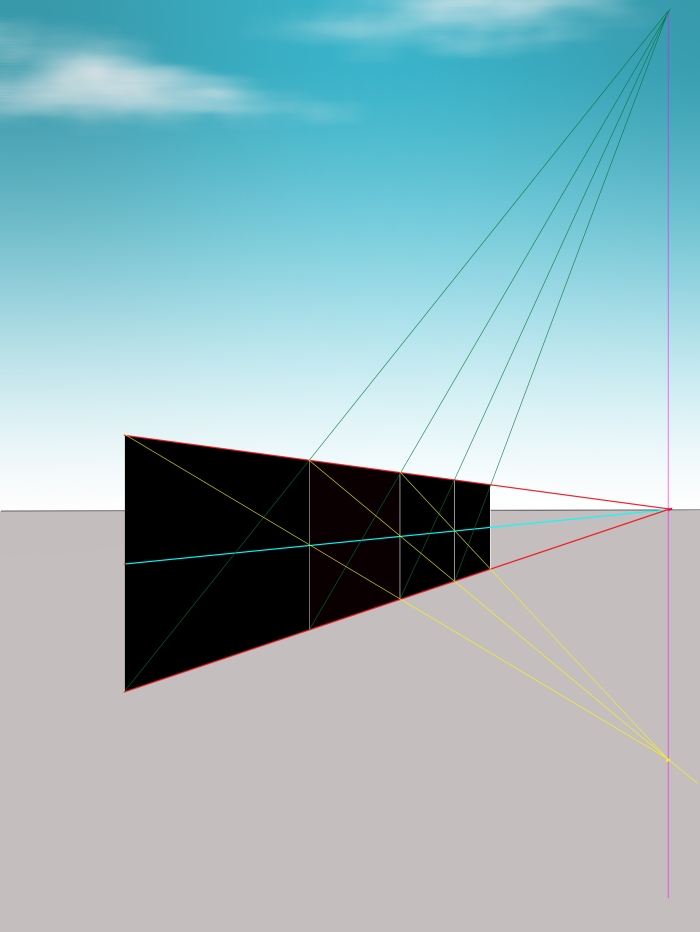

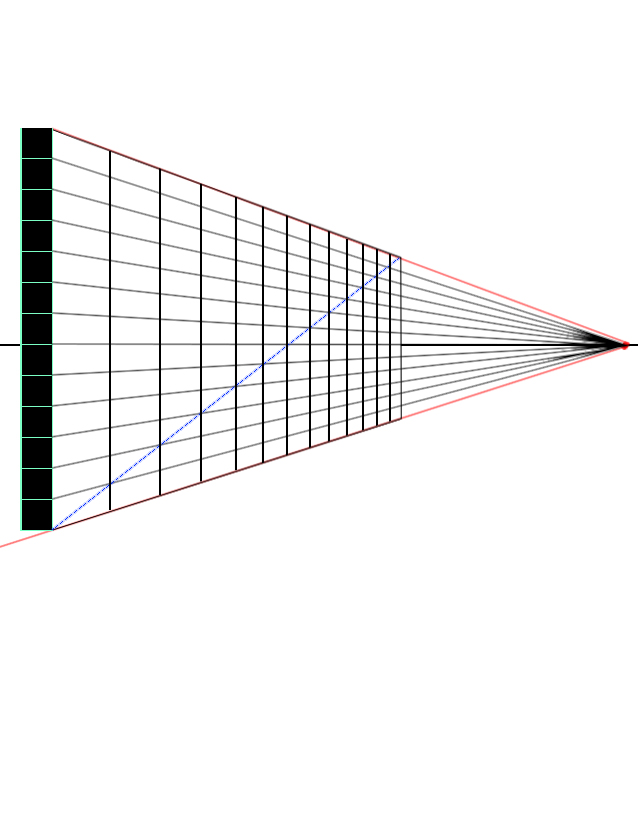

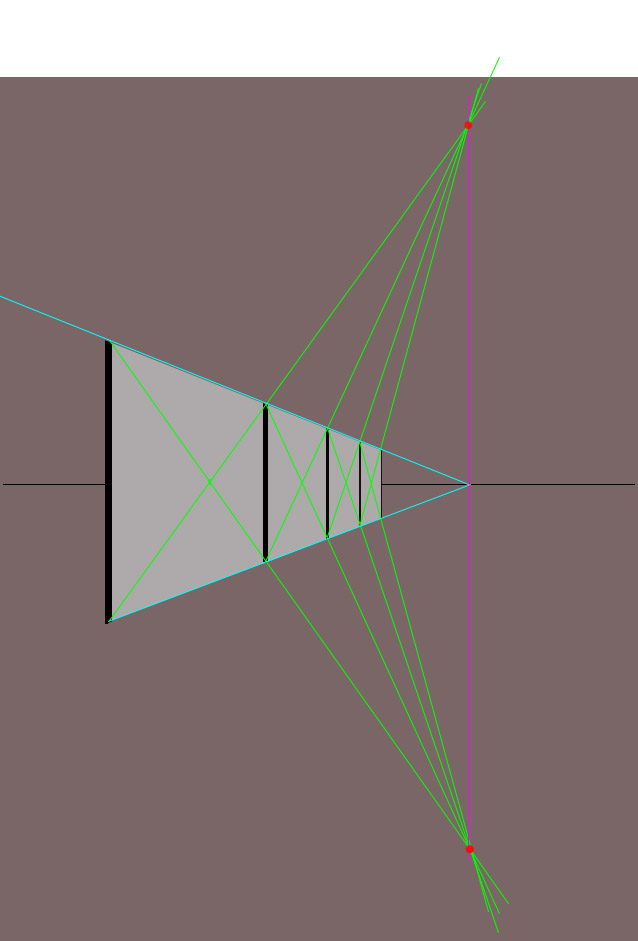

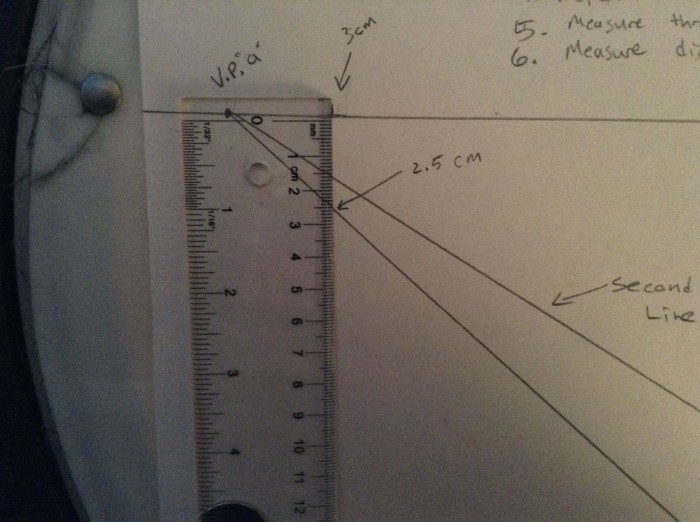

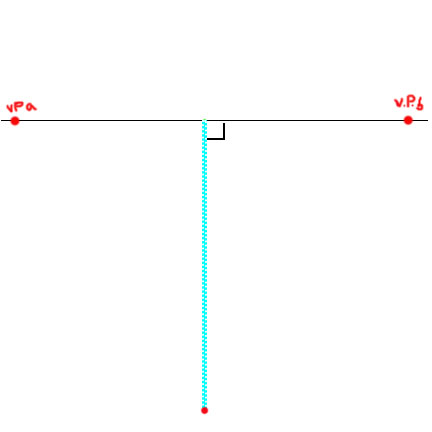

- At the wide edge, establish the vertical and horizontal planes which will be used as your measuring lines. (see last posting for further use of the horizontal and vertical lines as measurement guides)

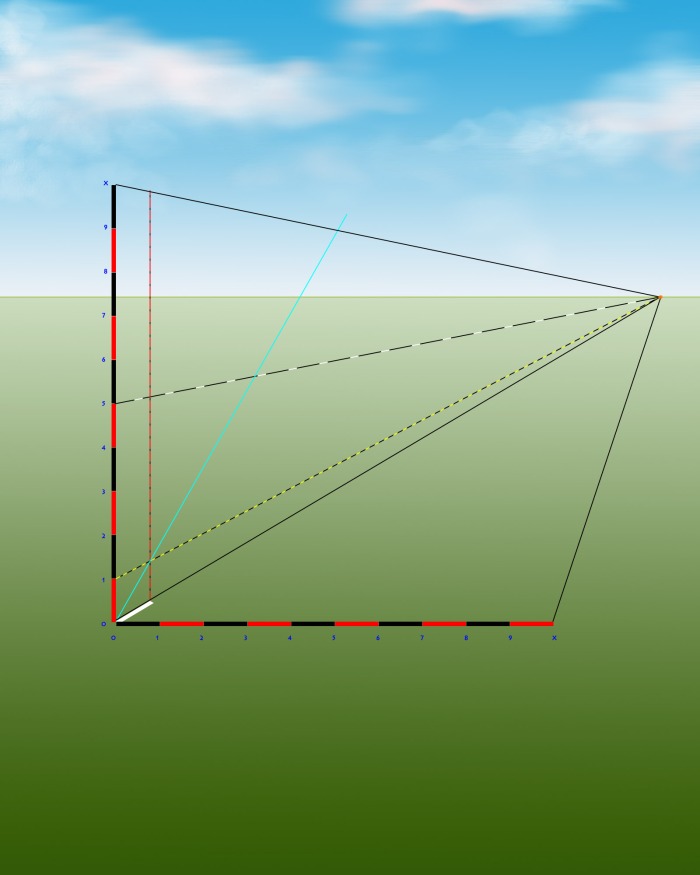

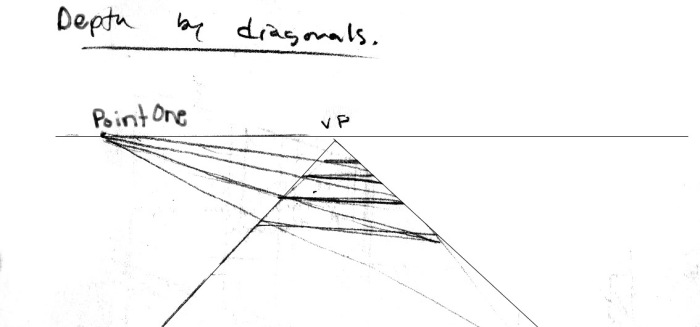

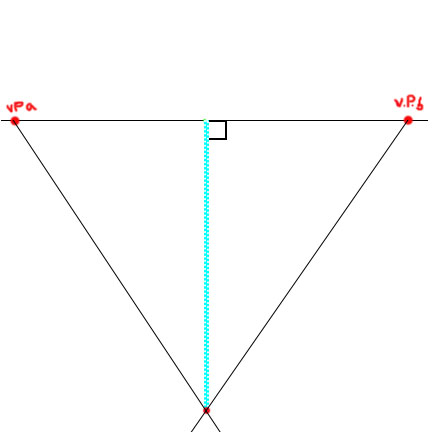

- Mark the VP and a new point, called the Measuring Point, just to the left or the right of the vertical scale. The MP can be on either side, but it must be close to the vertical line.

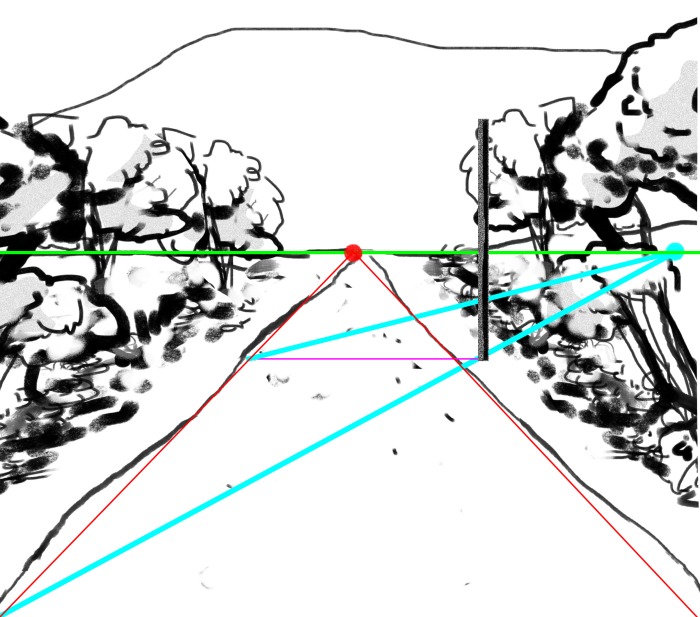

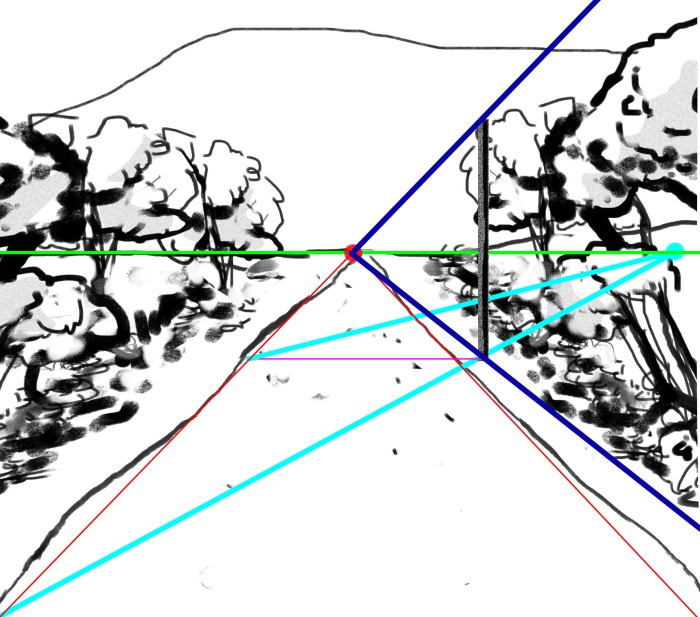

- Now, looking at the reference shot of Abu Simbel, one can see that there are 5 different sections in the sequence of Variable Spaces. They are as follows:

- Green Bracket: we will call these the FRAMES

- Red Bracket: we will call these the NICHES

- White Bracket: we will call this the PORTICO

- Purple Bracket: we will call these the JAMBS

- Blue Bracket: we will call this the DOORWAY

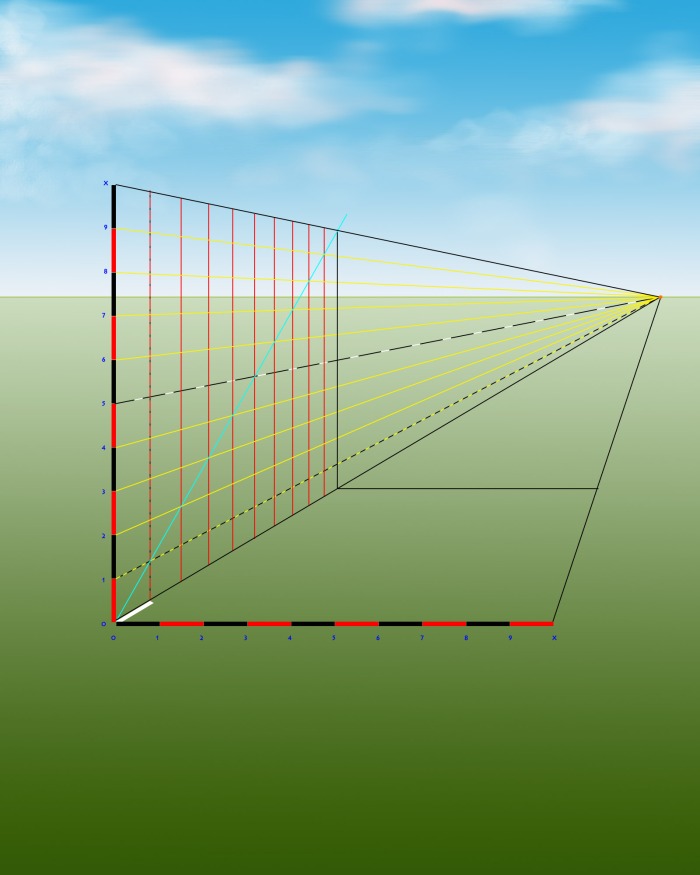

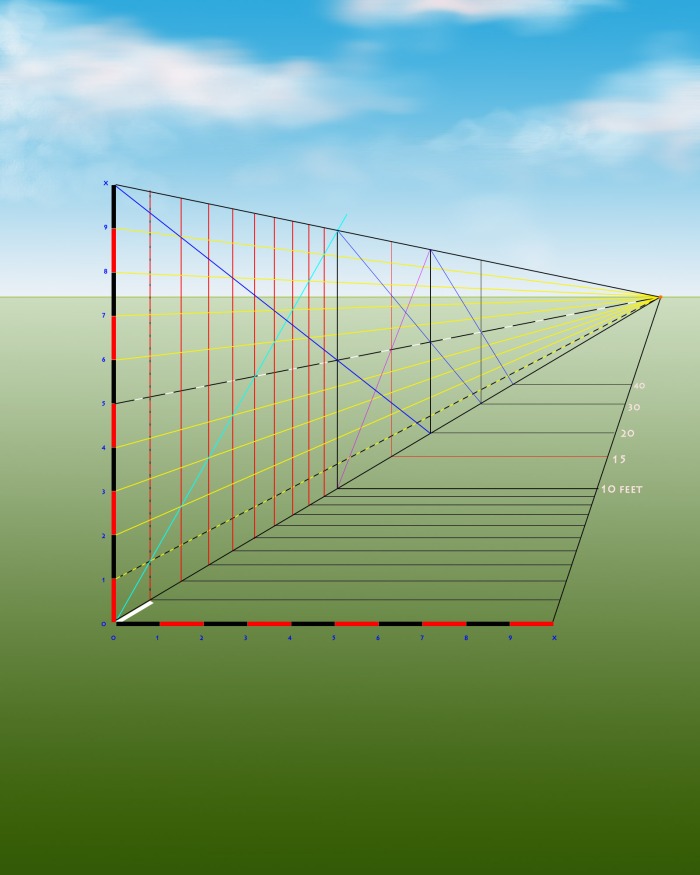

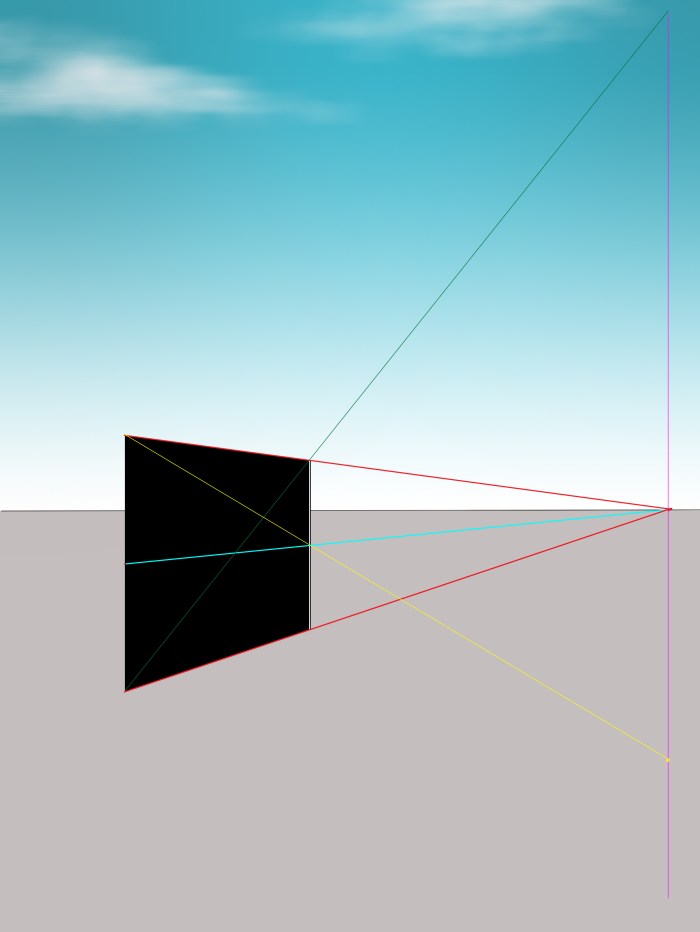

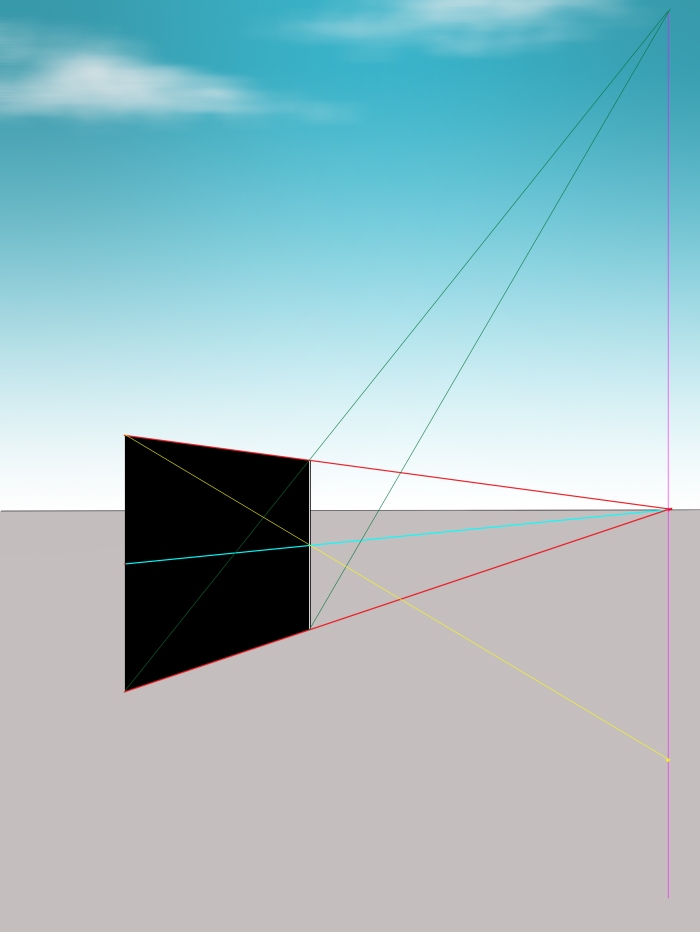

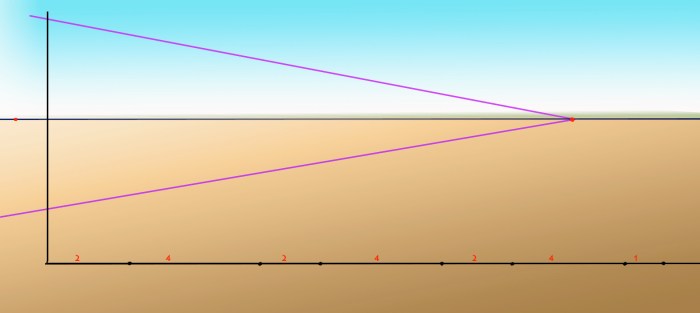

- Now, estimate the ratio of widths between the 5 spatial elements in the picture. For simplicity, let us say that the Frames to Niches are a 1:2 ratio in width, and the Jambs to Frames are also 1:2. (this means that the Niches are DOUBLE as wide as the Frames. So too is the relationship between the Jambs to the Frames; the Frames are DOUBLE as wide as the Jambs). Let us say the Jambs to the Doorway is 1:1.75. Once you have established a ratio of the sizes by eye, decide upon a base unit for the Frames (since most of the ratios refer to these). We shall say the Frames are 2 cm. Thus each section width is as follows:

- Frames: 2cm

- Niches: 4cm

- Portico: 3.75cm (two jambs + doorway)

- Jambs: 1cm

- Doorway: 1.75cm

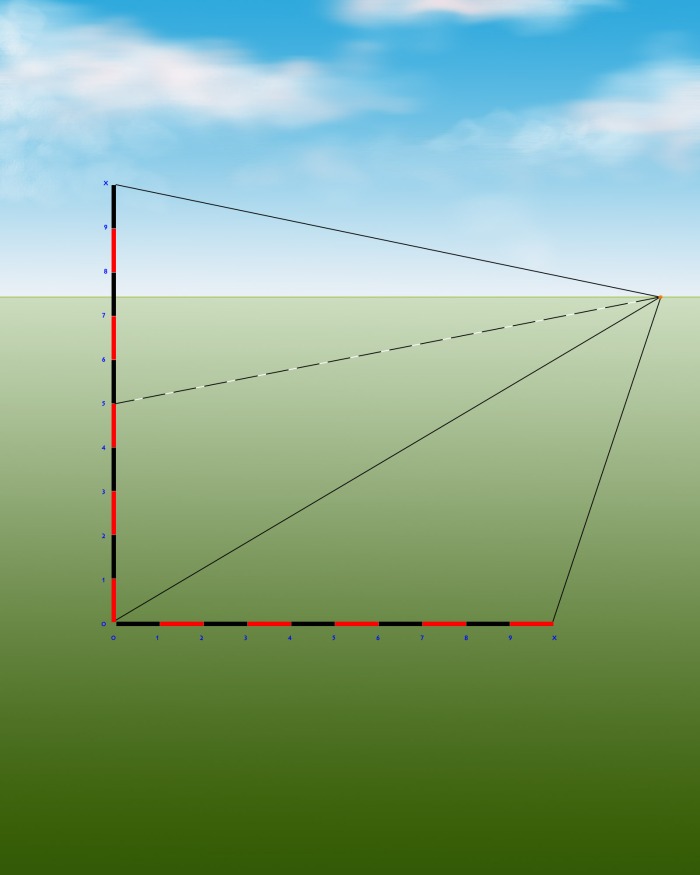

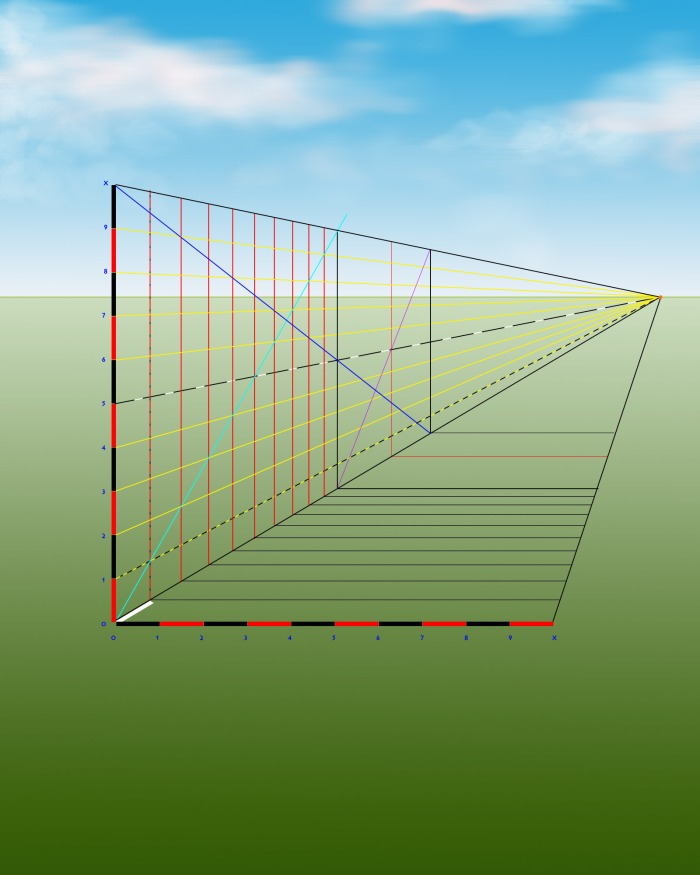

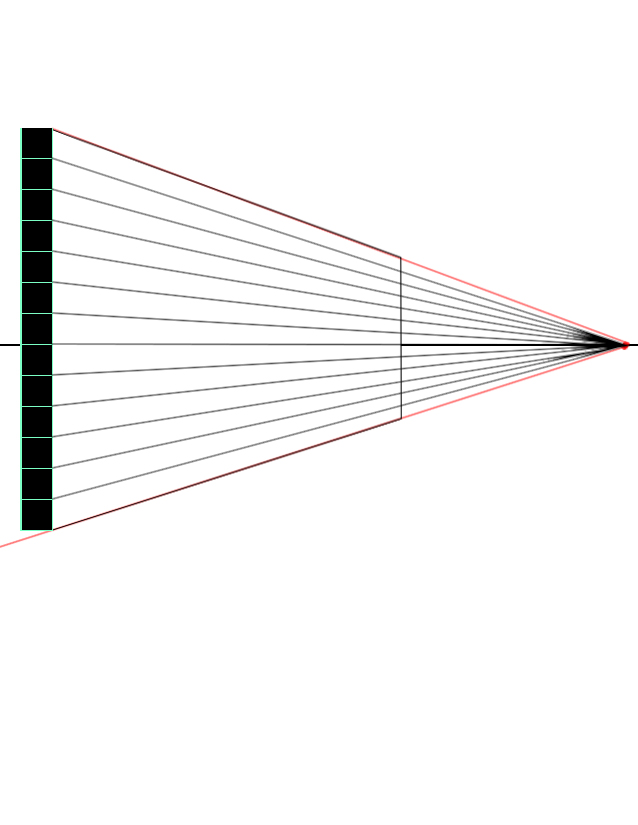

- Starting at the (0,0) point on the Vertical and Horizontal scale lines, lay out the measurements in the order that the sequence appears on the reference. The full sequence is not measured in this example, in order to accommodate the size of the image, and readability. In reality, one must layout the entire sequence on the horizontal Measuring Line.

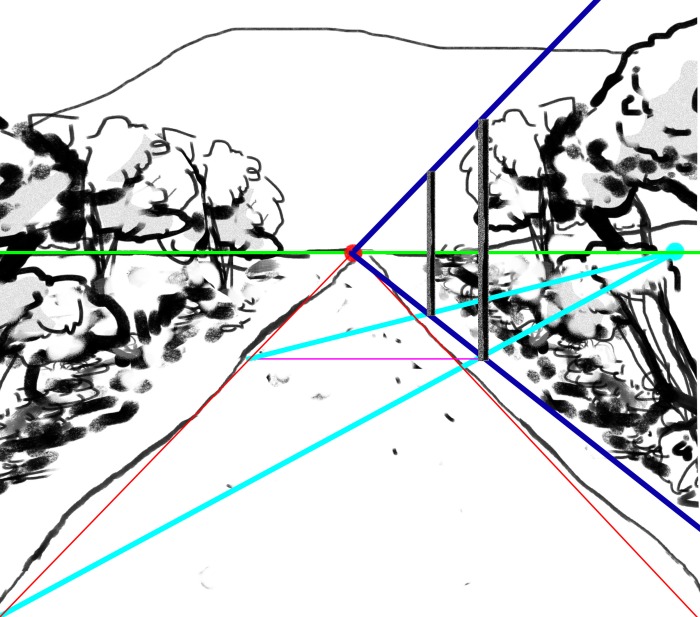

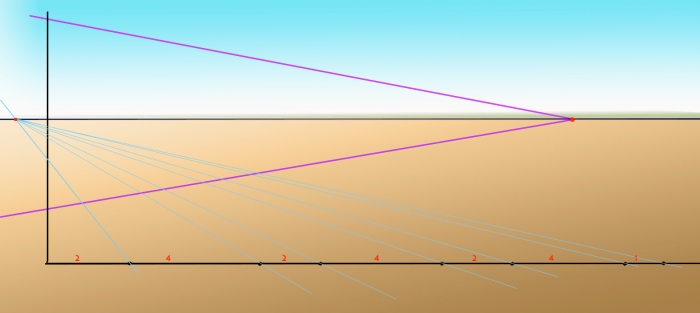

- Through the points on the Horizontal Measuring Line, cast new lines of measurement to the MP (Measuring Point)

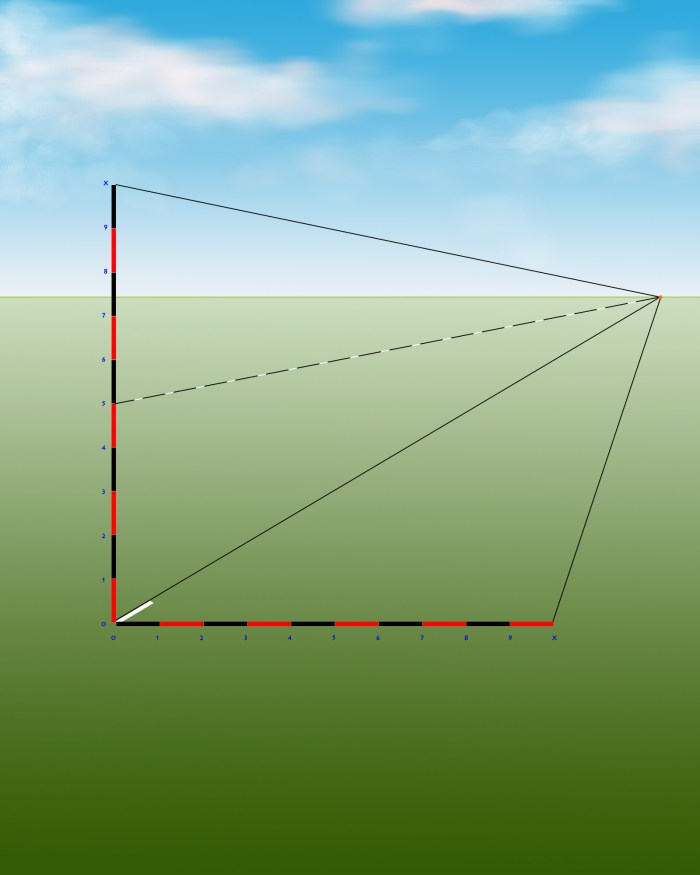

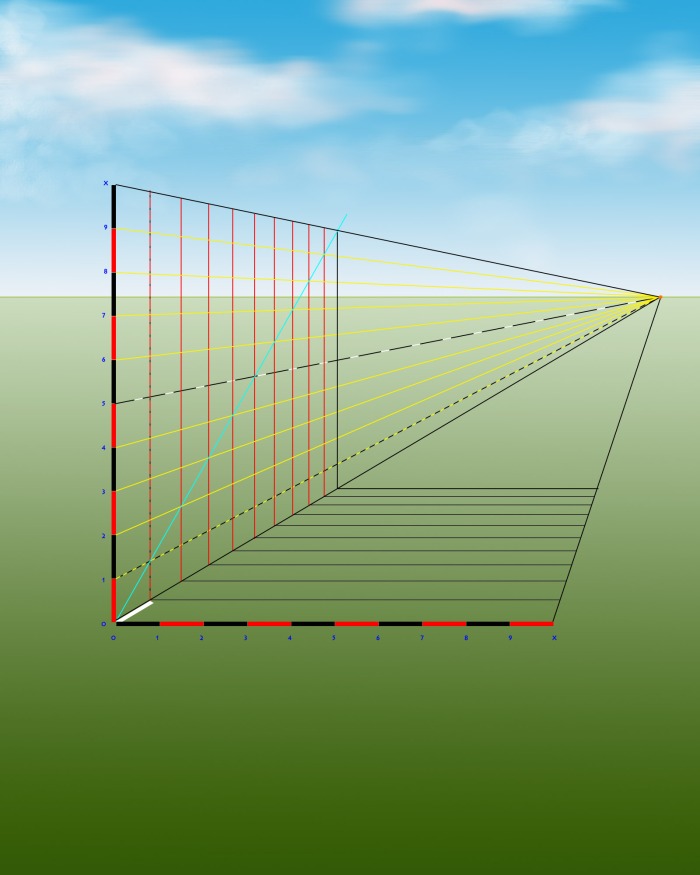

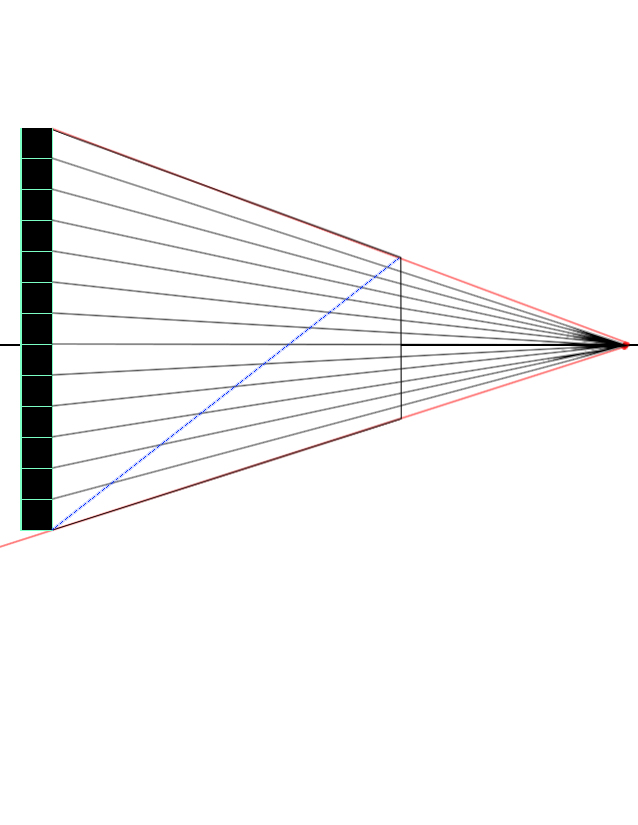

- The points where the cyan coloured Measuring Lines cross the bottom Perspectival Line will be the Variable Spaces on the monument, projected into perspective. A secondary (red) line of perspective is cast to accommodate for the sloping nature of the temple’s face, i.e. it is not 90°.

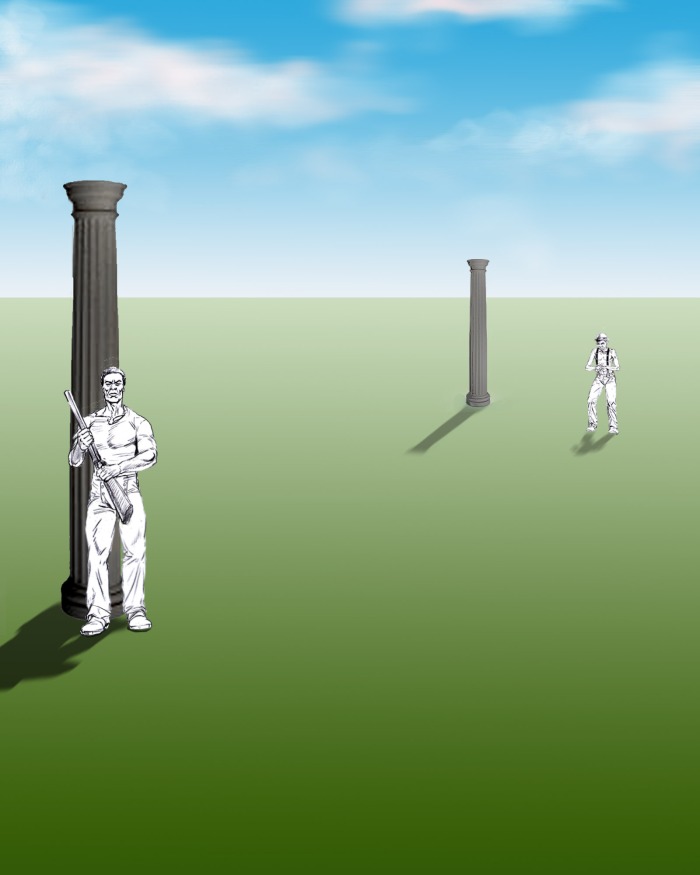

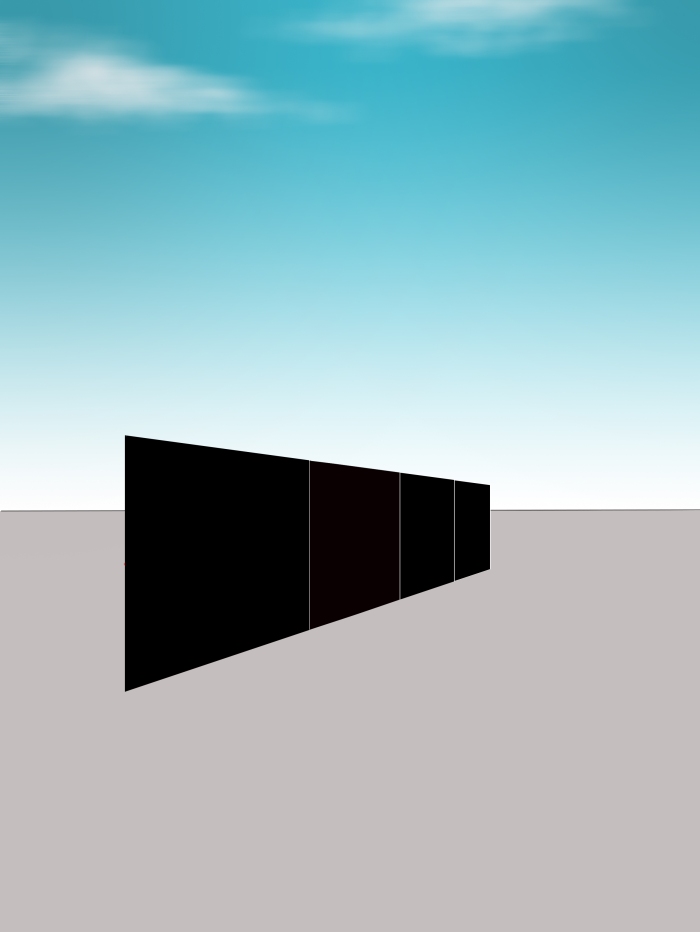

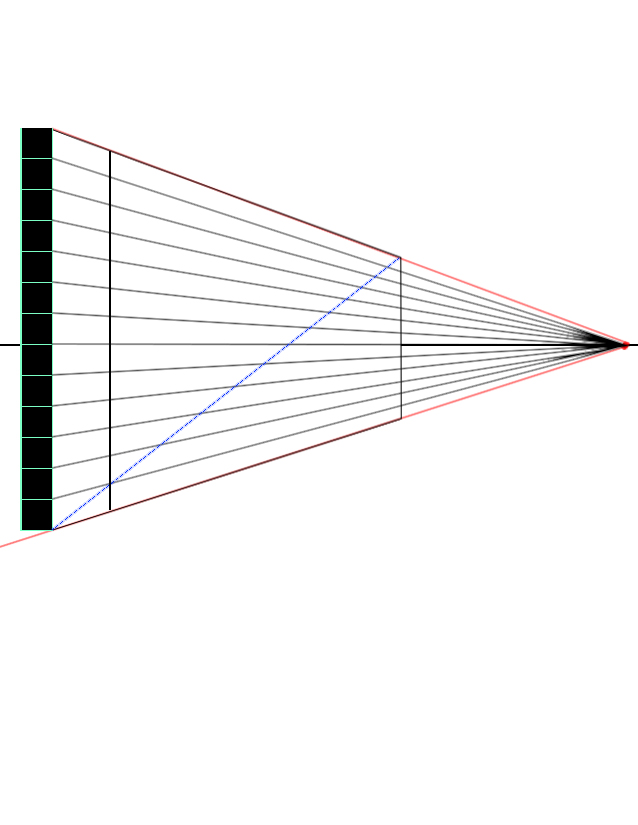

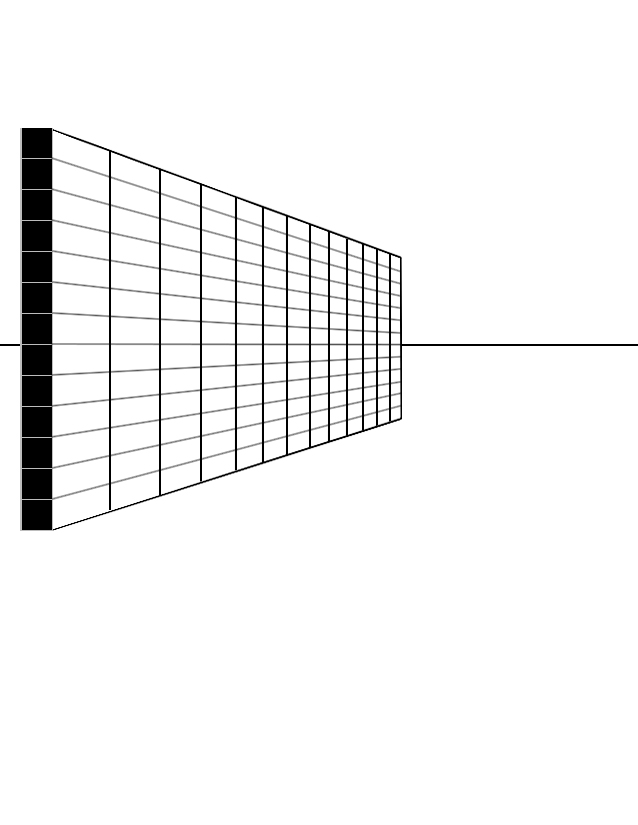

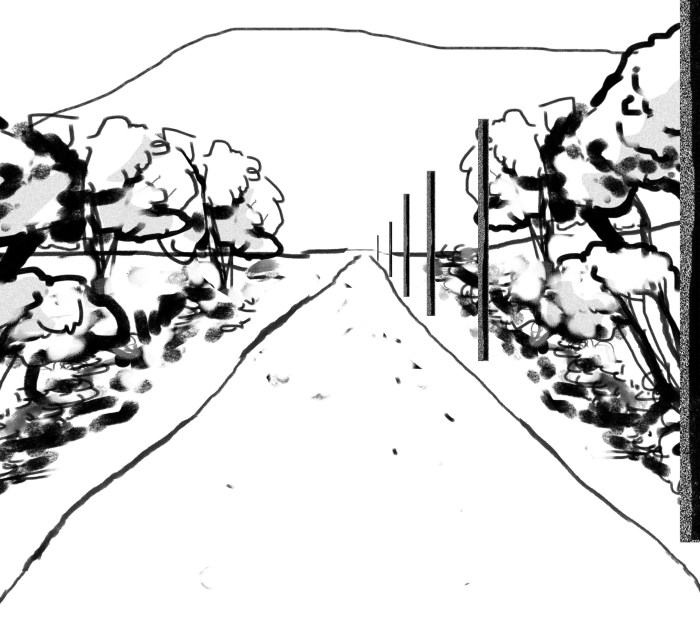

- Erase the guidelines and the new temple is drawn in the new perspective. Finish it to the level of detail that you desire.

In closing, I would like to apologize for not posting this on Sunday as per usual. I hope you are able to use this technique of projecting Variable Spaces within a Single Block. I also hope to see you next week.